Expert evidence in housing conditions claims

- Details

Jonathan McDonnell examines the role played by experts in housing conditions claims.

The expert

The expert sits in the centre of this Venn diagram.

Their expert report is evidence. That report contains both evidence of fact and opinion. They have to comply with the Civil Procedure Rules, and Practice Statements/Guidance Notes released by their regulator. They also have to have an understanding of the law, particularly in relation to s.9A/10/10A/11 of the Landlord and Tenant Act 1985. Being an expert is a difficult role that requires extensive training and experience to fulfil properly.

Different types of witnesses

There are broadly three categories of witnesses in housing disrepair cases:

- Lay witnesses of fact and limited opinion

- Lay witnesses that happen to be experts

- Part 35 experts

I use the word ‘lay’ to denote that the witness is not instructed pursuant to CPR Part 35.

Lay witness of fact

A lay witness of fact can give opinion evidence only in the following circumstances:

S3(2) Civil Evidence Act 1972 – It is hereby declared that where a person is called as a witness in any civil proceedings, a statement of opinion by him on any relevant matter on which he is not qualified to give expert evidence, if made as a way of conveying relevant facts personally perceived by him, is admissible as evidence of what he perceived.

Lay witnesses usually include the Claimant, and then repairs managers/housing officers.

Lay witness that happens to be an expert

What about lay witnesses that happen to be experts? Technical Officers working in-house for Local Authorities/Social Landlords spring to mind here. Their report, or evidence provided in a witness statement, is not compliant with Part 35, but they may very well be an expert. Their opinion is admissibly by virtue of:

S.3(1) of the Civil Evidence Act 1972 – Subject to any rules of court made in pursuance of this Act, where a person is called as a witness in any civil proceedings, his opinion on any relevant matter on which he is qualified to give expert evidence shall be admissible in evidence.

However, the giving of expert evidence by lay witnesses is qualified by the following:

(a) The need for the subject matter of the opinion to be such that a person without instruction or experience in the area of knowledge or human experience would not be able to form a sound judgment on the matter without the assistance of witnesses possessing special knowledge or experience in the area.

(b) The need for the subject matter of the opinion to form part of a body of knowledge or experience which is sufficiently organised or recognised to be accepted as a reliable body of knowledge or experience, a special acquaintance with which of the witness would render his opinion of assistance to the court. Plus, in some classes of case, for the recognised expertise to which the opinion relates to be governed by recognised standards and rules of conduct capable of influencing the court’s decision on any of the issues which it has to decide.

(c) The need for the witness to have acquired by study or experience sufficient knowledge of the subject to render his opinion of value in resolving the issue before the court.

But what is an expert? For this, we turn to Brendon International Ltd v Water Plus Ltd [2024] EWCA Civ 220 at [76] ‘… A leading case, from the criminal courts and dealing with handwriting, is R v Robb (1991) 93 Cr. App R 161. After referring to Lord Russell’s judgment in R v Silverlock [1894] 2 QB 766, Bingham LJ stated, at 165,

“ … the essential questions are whether study and experience will give a witness’s opinion an authority which the opinion of one not so qualified will lack, and (if so) whether the witness in question is peritus [skilled] in Lord Russell’s sense. If these conditions are met the evidence of the witness is in law admissible, although the weight to be attached to his opinion must of course be assessed by the tribunal of fact.”

[77] In the same case, at 166, Bingham LJ memorably contrasted the nature of an expert with that of a non-expert, when remarking that a defendant,

“… cannot fairly be asked to meet evidence of opinion given by a quack, a charlatan or an enthusiastic amateur.”

Does a lay witness have to give an independent expert opinion? Yes, but the consequences of not doing so are not the same as if the expert was a Part 35 expert:

[82] The Judge’s further reliance upon his view that Mr. Griffiths’ evidence was “self-serving for the defendants” was also an irrelevant factor so far as his determination as to whether Mr. Griffiths was qualified as an expert for the purposes of section 3. Questions of the independence of a person giving expert opinion evidence and whether their evidence is unbiased go to weight and not admissibility under section 3. Similarly, whilst a lack of detail to support Mr. Griffith’s opinions might cast doubt upon its accuracy or reliability, that goes to weight and not admissibility.

CPR Part 35 expert evidence

What is their role? This was recently set out quite plainly in Griffiths v TUI UK Ltd [2023] UKSC 48 at [36]: “It is trite law that the role of an expert is to assist the court in relation to matters of scientific, technical or other specialised knowledge which are outside the judge’s expertise by giving evidence of fact or opinion; but the expert must not usurp the functions of the judge as the ultimate decision-maker on matters that are central to the outcome of the case. Thus, as a general rule, the judge has the task of assessing the evidence of an expert for its adequacy and persuasiveness”

CPR r.35.2 sets out the definition of an expert for the purposes of Part 35: 35.2(1) A reference to an ‘expert’ in this Part is a reference to a person who has been instructed to give or prepare expert evidence for the purpose of proceedings.

What about independence in respect of Part 35 experts? Quite simply, their duty is to the Court and they need to act, and be seen to be acting, independently. CPR r.35.3 –

(1) It is the duty of experts to help the court on matters within their expertise.

(2) This duty overrides any obligation to the person from whom experts have received instructions or by whom they are paid.

Then from the commentary in the White Book 2025: ‘experts do not form part of a litigant’s ‘team’ with their role being the securing and maximising, or avoiding and minimising, a claim for damages.’

What are the consequences? Kennedy v Cordia (Services) LLP [2016] UKSC 6 at [51] Impartiality and other duties: If a party proffers an expert report which on its face does not comply with the recognised duties of a skilled witness to be independent and impartial, the court may exclude the evidence as inadmissible.

Also, wasted costs: in Phillips v Symes (A Bankrupt) (Expert Witnesses: Costs) [2004] EWHC 2330 (Ch); [2005] 1 W.L.R. 2043 the court held that it had the power to make a costs order against an expert whose evidence had caused significant expense to be incurred in circumstances where he had acted “in flagrant reckless disregard of his duties to the Court.”

Pre-action protocol for housing conditions claims (England)

Paragraphs of note for the purpose of this article include:

1.3 If a claim proceeds to litigation, the court will expect all parties to have complied with the Protocol. The court has power to order parties who have unreasonably failed to comply with the Protocol to pay costs or to be subject to other sanctions.

3.4 The Protocol should be followed in all cases, whatever the value of the damages claim.

5.2 The tenant should send to the landlord a Letter of Claim at the earliest reasonable opportunity. A specimen Letter of Claim is at Annex A. The letter may be suitably adapted as appropriate. The Letter of Claim should contain the following details–

(b) details of the defects, including any defects outstanding, in the form of a schedule, if appropriate

(h) the proposed expert

6.2 The landlord should normally reply to the Letter of Claim within 20 working days of receipt. Receipt is deemed to have taken place two days after the date of the letter – disclosure and nomination of expert response

6.3 The landlord must also provide a response dealing with the issues set out below, as appropriate. This can be provided either within the response to the Letter of Claim or within 20 working days of receipt of the report of the single joint expert or receipt of the experts’ agreed schedule following a joint inspection

Paragraph 7 – experts

(a) Parties are reminded that the Civil Procedure Rules provide that expert evidence should be restricted to that which is necessary and that the court’s permission is required to use an expert’s report. The court may limit the amount of experts’ fees and expenses recoverable from another party.

(b) When instructing an expert, the parties must have regard to CPR 35, CPR Practice Direction 35 and the Guidance for the Instruction of Experts in Civil Claims (2014)

7.1(d) The expert should be instructed to report on all adverse housing conditions which the landlord ought reasonably to know about, or which the expert ought reasonably to report on. The expert should be asked to provide a schedule of works, an estimate of the costs of those works, and to list any urgent works.

Linked to 7.1(d) – paragraph 6.5 – The Letter of Claim and the landlord’s response are not intended to have the same status as a statement of case in court proceedings. Matters may come to light subsequently which mean that the case of one or both parties may be presented differently in court proceedings. Parties should not seek to take advantage of such discrepancies, provided that there was no intention to mislead.

7.2 (a) If the landlord does not raise an objection to the proposed expert or letter of instruction within 20 working days of receipt of the Letter of Claim, the expert should be instructed as a single joint expert, using the tenant’s proposed letter of instruction. (See Annex B for a specimen letter of instruction to an expert.)

(b) Alternatively, if the parties cannot agree joint instructions, the landlord and tenant should send their own separate instructions to the single joint expert. If sending separate instructions, the landlord should send the tenant a copy of the landlord’s letter of instruction with their response to the Letter of Claim.

7.3 (a) If it is not possible to reach agreement to instruct a single joint expert, even with separate instructions, the parties should attempt to arrange a joint inspection, meaning an inspection by different experts instructed by each party to take place at the same time. If the landlord wishes their own expert to attend a joint inspection, they should inform both the tenant’s expert and the tenant’s solicitor.

Urgent cases –

7.5 The Protocol does not prevent a tenant from instructing an expert at an earlier stage if this is considered necessary for reasons of urgency. Appropriate cases may include–

(a) where the tenant reasonably considers that there is a significant risk to health and safety;

(b) where the tenant is seeking an interim injunction; or

(c) where it is necessary to preserve evidence.

Lancastle v Curo Group (Albion) Limited (2025) EWCC 48 – see Giles Peaker’s excellent blogpost on this: Tales from the Housing Conditions wars. Part 1 – Nearly Legal: Housing Law News and Comment

Should an expert be giving an opinion as to liability?

In my view, no. But this is practice wide. I find support in my opinion based on Annex B of the Protocol (letter of instruction to expert) which makes no mention of asking the expert to give an opinion as to liability. Respectfully, experts are not experts of the law.

The RICS Practice Note on acting as expert witnesses and its guidance note (Surveyors acting as expert witnesses_Feb2023amend.pdf) says at GN7.4 It is recommended that you do not express, as your own opinion, an interpretation of statute or case law unless qualified to do so. If your conclusions depend upon assumptions as to such matters, however, you should identify the assumption being made.

In reality, what an expert is really saying is that a certain defect falls within the ambit of one of the Defendant’s repairing obligations. It may be worth clarifying this in the report, or at the very least changing the title of the column in the Scott Schedule to ‘suggested liability’.

Remember, a key point is that an expert’s opinion does not usurp the functions of the Court: Griffiths v TUI UK Ltd [2023] UKSC 48 at [36] – ‘It is trite law that the role of an expert is to assist the court in relation to matters of scientific, technical or other specialised knowledge which are outside the judge’s expertise by giving evidence of fact or opinion; but the expert must not usurp the functions of the judge as the ultimate decision-maker on matters that are central to the outcome of the case. Thus, as a general rule, the judge has the task of assessing the evidence of an expert for its adequacy and persuasiveness.’

Causes of action

The main causes of action are borne out of contract law. Terms are either express (written within the tenancy conditions) or implied (inserted into the tenancy conditions). Other causes of action include a duty under s.4 Defective Premises Act 1972, and the obligation to grant the tenant quiet enjoyment of the Property/not to derogate from grant. As far as experts in these cases are concerned, their focus very much should be on the implied and express terms.

If an expert is asked as to give an opinion as to whether an item of disrepair falls within the Defendant’s repairing obligations, it helps if the expert has read the tenancy conditions. Solicitors must therefore remember to send these to the experts.

I don’t intend to write about s.11 in this article as most practitioners are well familiar with its contents.

S.9A LTA 1985

Again, I will not go into too much detail in this article as this authority has been around for a while now.

Two really important points were clarified just over a year ago in Jillians v Red Kite Community Housing (Oxford CC 24th September 2024):

- Whether a hazard must be designated as a category 1 or category 2 hazard to be actionable; and

- The meaning of unfitness for human habitation.

Meaning of hazard

S.10(1) LTA 1985 sets out a number of conditions the Court will consider, such as freedom from damp, ventilation, and natural lighting. It also makes reference to ‘in relation to a dwelling in England, any prescribed hazard’.

S.10(2) provides ‘prescribed hazard means any matter or circumstance amounting to a hazard for the time being prescribed in regulations made by the Secretary of State under section 2 of the Housing Act 2004.’

So, we jump over to s.2 Housing Act 2004. S.2(1) HA 2004 provides:

In this Act—

“category 1 hazard” means a hazard of a prescribed description which falls within a prescribed band as a result of achieving, under a prescribed method for calculating the seriousness of hazards of that description, a numerical score of or above a prescribed amount;

“category 2 hazard” means a hazard of a prescribed description which falls within a prescribed band as a result of achieving, under a prescribed method for calculating the seriousness of hazards of that description, a numerical score below the minimum amount prescribed for a category 1 hazard of that description; and

“hazard” means any risk of harm to the health or safety of an actual or potential occupier of a dwelling or HMO which arises from a deficiency in the dwelling or HMO or in any building or land in the vicinity (whether the deficiency arises as a result of the construction of any building, an absence of maintenance or repair, or otherwise).

Linked to the Housing Act 2004 are the Housing Health and Safety Rating System (England) Regulations 2005, in which Schedule 1 lists 29 hazards (The Housing Health and Safety Rating System (England) Regulations 2005).

What did Jillians confirm? HHJ Clarke confirmed:

‘Mr Strelitz submits that it is not open to me to make a finding on unfitness for human habitation as I have no expert evidence on the point. He accepts that I have photographs showing the quantity of mould and where it is, but submits that I lack expert opinion on whether that level of mould in that position is hazardous to health in the quantity it is present and who needs to carry out HHSRS calculations to establish whether it is a Category 1 or Category 2 Hazard. I do not agree.

I accept Mr Murray’s submission that ‘hazard’ as defined in section 2 of the Housing Act 2004 is about the risk of harm to the health and safety of an occupier of a dwelling, which arises from a deficiency in the dwelling, not measurable and measured harms. He draws a distinction between section 9A LTA and section 11 in this respect, as pursuant to section 11 LTA a ‘risk’ of disrepair is not actionable. Under section 9A LTA a risk of harm is actionable and that is what I am required to assess by determining whether it is reasonably suitable for occupation.’

Unfitness for human habitation

Whilst only a persuasive authority, it confirmed that the test set out in Rendlesham Estates v Barr [2014] EWHC 3968 (TCC) applied:

(a) be capable of occupation for a reasonable time without risk to the health or safety of the occupants: where a dwelling is or is part of a newly constructed building, what is a reasonable time will be a question of fact (it may or may not be as long as the design life of the building); and

(b) be capable of occupation for a reasonable time without undue inconvenience or discomfort to the occupants.

This gives a clearer benchmark to the caveat imposed by s.10 LTA 1985: ‘and the house [or dwelling] shall be regarded as unfit for human habitation if, and only if, it is so far defective in one or more of those matters that it is not reasonably suitable for occupation in that condition.’

Awaab’s law under s.10A LTA 1985 and The Hazards in Social Housing (Prescribed Requirements) (England) Regulations 2025

The Gov.UK draft guidance is very helpful (Awaab’s Law: Draft guidance for social landlords – GOV.UK). It applies from 27th October 2025.

Landlords must address all ‘emergency hazards’ and also damp and mould hazards that ‘present a significant risk of harm’. Other hazards listed in HHSRS Regs 2005 Schedule 1 to be introduced in 2026 and 2027 (apart from overcrowding)

Awaab’s law implies a term into the contract (much like s.11 and s.9A LTA 1985) that requires social landlords to comply with the requirements.

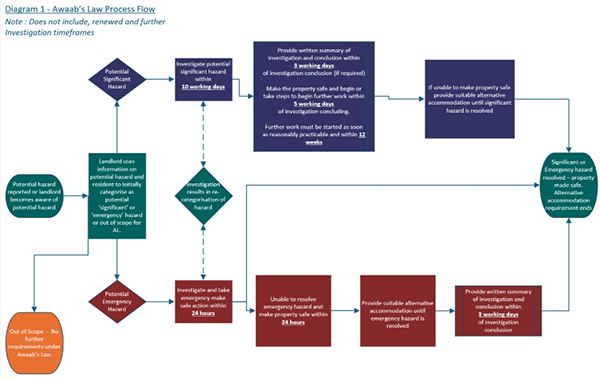

A helpful overview of the process is as follows:

This article will not be a full overview of the law. There are numerous stress points within the Regulations, such as how they interact with the Pre-Action Protocol.

Awaab’s Law uses a person-centred approach: a more straightforward assessment should be made which considers the tenant’s circumstances when assessing the risks presented by a hazard. Awaab’s Law therefore does not require a hazard to be at category 1 level under HHSRS in order to be in scope as there may be instances where a particular tenant is at a greater risk from hazardous conditions. For example, a tenant with age or health related vulnerabilities may be at significant risk from a home affected by damp and mould, even if it were scored as a category 2 hazard under the HHSRS.

The requirements are set out within Regulation 3(2) as follows:

- be a part of buildings or land for which the social landlord is responsible

- be in the landlord’s control to fix

- not be damage that is a result of breach of contract by the tenant

- result from defects, disrepair or lack of maintenance

- be a significant or emergency hazard

A few points of note jump out to me.

Regulation (2)(b) provides ‘arises from a deficiency in the social home, or in any building, part of a building or land in the vicinity of the social home, for which the lessor is responsible’

The use of the word ‘deficiency’ puts an end once and for all to the defence that if an issue falls outside of the remit of s.11 LTA 1985 (forming part of the structure or exterior), it must also not be actionable as a hazard. In my view, this stance taken by Defendants was never right in law in the first place.

An example given in the Guidance document is in respect of a lack of thermal insulation in the structure of the home that leads to excessive mould growth. If this allegation featured in a set of Particulars that were being defended today, it would almost certainly be defended on the basis that it is an improvement, not repair, based on the current legislative framework. That defence will have very little merit under Awaab’s Law.

Another major issue is the definition of ‘significant’ and ’emergency’ hazards, and who is competent to inspect for them.

Significant and emergency hazards

“significant hazard” means, in relation to a social home, a relevant hazard that poses a significant risk of harm to the health or safety of an occupier of the social home;

“emergency hazard” means, in relation to a social home, a relevant hazard that poses an imminent and significant risk of harm to the health or safety of an occupier of the social home;

“significant risk of harm” means a risk of harm to the occupier’s health or safety that a reasonable lessor with the relevant knowledge would take steps to make safe as a matter of urgency (but not within 24 hours);

“imminent and significant risk of harm” means a risk of harm to the occupier’s health or safety that a reasonable lessor with the relevant knowledge would take steps to make safe within 24 hours.

Significant hazards

The guidance helpfully sets out the following: what a ‘reasonable lessor’ would do will depend on the circumstances of the individual case and should reflect the nature of the problem, tenants’ needs and the scale of works required. Landlords will therefore need to factor in individual circumstances, including the age and physical and mental health of the tenants to assess the likelihood of harm materialising and the potential severity of that harm in the specific circumstances. A tenant does not necessarily have to have a specific vulnerability for a hazard to be deemed a significant hazard: some hazards can pose a danger to anyone. A tenant does not need to provide medical evidence, although landlords should take this into account if it is provided.

Social landlords should use Awaab’s Law guidance alongside a range of available information to inform decision making including government guidance, such as guidance on damp and mould, and the HHSRS guidance as well as information about the tenant which they already hold or find out about when the hazard is reported. Social landlords may wish to adopt a risk matrix approach within their organisations to help with determining whether there is a significant hazard.

Whilst this is just a very rough example that I’ve put together, a matrix may include some or all of the following factors:

|

Factor |

Low Risk |

Medium Risk |

High Risk |

|

Nature of Hazard |

Minor inconvenience, unlikely to cause harm (e.g. small patch of condensation mould in a well-ventilated room) |

Hazard may cause discomfort/illness over time f unresolved (e.g. persistent damp smell, recurring minor leaks) |

Hazard presents an immediate or serious risk to health or safety (e.g. extensive black mould on walls) |

|

Tenant Characteristics |

Tenant is generally healthy, no additional needs, able to manage short-term issues |

Tenant has some vulnerabilities (young children, elderly, limited mobility) increasing the likelihood of harm |

Tenant has significant vulnerabilities (serious respiratory condition, mental health issues worsened by housing, very young children or frail elderly) |

|

Severity of Harm |

Minor health effects or inconvenience (e.g. mild irritation) |

Moderate health impacts (e.g. asthma flare-ups, stress, sleep disturbance) |

Severe or life-threatening impacts (e.g. risk of hospitalisation, carbon monoxide exposure, hypothermia) |

Emergency hazards

Examples include:

- Gas leaks

- Broken boilers

- Total loss of water supply

- Significant leaks

- Broken external doors or windows that present a risk to home security

- Prevalent damp and/or mould that is having a material impact on an occupier’s health, for example their ability to breathe

The Guidance document sets out a helpful scenario:

The tenant reported issues with damp and mould to the landlord. The problem was widespread and most severe in the only bedroom, particularly from the window area extending behind the bed. The tenant also informed the landlord that she was pregnant and experiencing symptoms such as wheezing and shortness of breath.

Based on the initial report, the landlord assessed the situation as a potential emergency hazard requiring further investigation to determine the extent and cause. Accordingly, the landlord arranged for a contractor to attend within 24 hours to investigate the emergency hazard and take action to make the Property safe. The contractor visited early the next working day.

In this scenario, a reasonable landlord would likely have classified the issue as an emergency hazard, based on the location of the mould, the contractor’s investigation findings and the tenant’s reported vulnerability and symptoms. The presence of mould in areas such as bedrooms or living spaces, particularly where those with pre-existing health conditions reside, poses a serious and immediate risk to health.

Competent investigator – regulation 2

“competent investigator” means a person that, in the reasonable opinion of the lessor, has the skills and experience necessary to determine whether a social home is affected by a significant hazard or emergency hazard

The guidance provides: ‘The social landlord must ensure an investigation is conducted by a person who (in the reasonable opinion of the social landlord) is competent to do so. This should be a person with the skills and experience necessary to determine whether the social home is affected by a significant or emergency hazard. A social landlord should use properly qualified specialists to investigate where relevant.’

The addition of the words ‘in the reasonable opinion of the lessor’ confuses me. I do not know why this was included as part of the definition. It creates an additional and unnecessary layer of confusion. A competent inspector is not someone that has the skills and experience necessary to determine whether a social home is affected by a significant hazard or emergency hazard. It is someone that in the reasonable opinion of the social landlord has the skills and experience necessary to determine whether a social home is affected by a significant hazard or emergency hazard. It may sound like only a minor difference, but it is an important one.

Does the burden of proof shift? Is it for the Defendant to prove to the Court that the person they sent was a competent inspector in their reasonable opinion? How does a tenant challenge the landlord’s reasonable opinion? Who is the landlord going to send to the Property to complete these inspections? Housing officers with HHSRS training? Would these be lay witnesses who happen to be experts? Will the landlord have to provide the qualifications and experience of anyone that is completing an Awaab’s law assessment?

What does this mean for experts? Well, in my view, they are going to have to fully understand the differences between significant and emergency hazards. They are going to need disclosure of the vulnerabilities or disabilities of the occupants. Data protection law will need to be complied with. Will they need to complete further training in respect of the HHSRS if they haven’t already? Possibly, but it is acknowledged that an assessment to determine whether a hazard is category 1 or category 2 is not required, much like HHJ Clarke clarified in Jillians.

It is likely experts will be asked to give an opinion as to whether a hazard in a Property is a significant or emergency hazard. How the Court resolves a dispute between a competent inspector (in the reasonable opinion of the landlord) and that of an independent expert instructed by the tenant remains to be seen.

Relevant safety works

It is important to note that a finding of an emergency or significant hazard triggers the requirement for relevant safety works to be completed. This is distinct to preventative works, that may come later.

The example given in the Guidance is helpful: The tenant reported damp and mould in their Property, a one-bedroom flat located on the top floor of a converted house. This has increased following heavy rainfall during the winter months and the tenant had reported that several roof tiles had been displaced. The landlord identifies this as a potential significant hazard and schedules an investigation within 10 working days. The investigation finds that the damp and mould is being exacerbated by the damage to the roof, which will require scaffolding to fix.

In the scenario described, the landlord would need to take action to make the Property safe within 5 working days, which could be undertaking a mould wash to remove the immediate hazard. They will also need to start work to fix the damage to the roof to prevent the hazard recurring in the same time period. In this scenario the landlord may not be able to start the work straight away if scaffolders are not available, so they should take steps towards this happening within 5 working days by booking scaffolders and other contractors to start as soon as reasonably practicable, and within 12 weeks of the investigation concluding.

Decanting the tenant and occupiers from the Property

If the social landlord is unable to complete the relevant safety work within the initial remediation period (5 working days from the completion of the investigation that identified the hazard for a significant hazard or 24 hours for an emergency hazard), they must secure the provision of suitable alternative accommodation at their expense, until the relevant safety work has been completed.

The Guidance goes on to say:

Where the social landlord must secure the provision of suitable alternative accommodation they must take into account the needs of the household to assess what is ‘suitable’. This could include: ensuring adequate space for the tenants, including appropriate number of bedrooms given the tenants’ family make up location of the Property, considering distance from tenants’ workplaces or schools, considering disability or medical needs to ensure accommodation is accessible for tenants with mobility issues, length of stay in alternative accommodation.

Accommodation that is suitable for a short period may not be suitable for a longer period. For example, if a family of four is provided accommodation for one night only whilst an emergency hazard is addressed in their home, a hotel may be suitable. If relevant safety work is estimated to take six weeks to complete, a hotel without adequate facilities and space would not be suitable due to lack of space and facilities such as a kitchen to prepare meals

One large social landlord has already indicated that it does not have the resources to comply with this requirement. Nonetheless, the death of Awaab has resulted in tenant safety taking priority over financial resources. Landlords are required to comply with the law.

It will be interesting to see what awards of general damages are made for tenants that are decanted. I imagine landlords will offer nominal sums of money in full and final settlement of claims to cover the inconvenience of a decant. This may have the effect of preventing the tenant from bringing a future claim under the res judicata principle.

Experts are likely to be required to add more detail to their schedule of works, detailing whether certain works are safety works or preventative works. More detail on the likely time to complete works is likely, as is more detail in respect of why a decant from the Property is or is not required.

Ensuring robust court-compliant reports

The following list is a summary of some of the key points taken from CPR Part 35, Practice Direction 35, and the commentary to the White Book 2025.

- Necessary knowledge and experience – ‘he or she can draw on the general body of knowledge and understanding of the relevant expertise’

- Impartial in the presentation and assessment of the evidence.

- An expert witness should state the facts or assumptions on which their opinion is based. They should not omit to consider material facts which could detract from their concluded opinion.

- An expert witness should make it clear when a particular question or issue falls outside their expertise.

- If an expert’s opinion is not properly researched because they consider that insufficient data are available then this must be stated with an indication that the opinion is no more than a provisional one.

- When they receive new information or have considered the opinion of another expert, they should be prepared to reconsider their own opinion and even, if appropriate, change their mind, and should do so at the earliest opportunity.

- The ambit of an expert’s duty to the court includes the duty to cover and give opinions upon the whole of the relevant subject matter and not to select only the evidence which supports the case of the party instructing them.

- Experts of like discipline should have access to the same material.

- It is not for an independent expert to indicate which version of the facts they prefer.

- Should material emerge close to trial such that an expert considers that further analysis, consideration or testing is required, his or her opposite number should be notified as soon as possible. Only in exceptional circumstances rendering it unavoidable should an expert produce a further report during a trial that takes the other side by surprise.

- Experts ought not to embark on a fact-finding exercise. Fact-finding is the court’s role, not the expert’s.

- While an expert may properly research an area on which they are to give evidence, and in so doing seek the views of others in the field or colleagues who work with them, they may only do so in order to improve their knowledge, i.e. to “enhance” their expertise. They must not do so to educate themselves for the purposes of the proceedings, i.e. an “expert” does not become an expert by obtaining knowledge of a field in the course of being instructed in a case.

- PD 35 para 3.2 –

3.2 An expert’s report must—

(1) give details of the expert’s qualifications;

(2) give details of any literature or other material which has been relied on in making the report;

(3) contain a statement setting out the substance of all facts and instructions which are material to the opinions expressed in the report or upon which those opinions are based;

(4) make clear which of the facts stated in the report are within the expert’s own knowledge;

(5) say who carried out any examination, measurement, test or experiment which the expert has used for the report, give the qualifications of that person, and say whether or not the test or experiment has been carried out under the expert’s supervision

- 3.2(6) where there is a range of opinion on the matters dealt with in the report—

(a) summarise the range of opinions; and

(b) give reasons for the expert’s own opinion;

I don’t often see compliance with this paragraph. This is an improvement most experts can make.

Guidance for the Instruction of Experts in Civil Claims 2014

30. Experts should try to ensure that they have access to all relevant information held by the parties, and that the same information has been disclosed to each expert in the same discipline. Experts should seek to confirm this soon after accepting instructions, notifying instructing solicitors of any omissions.

56. Where tests of a scientific or technical nature have been carried out, experts should state:

a. the methodology used; and

b. by whom the tests were undertaken and under whose supervision, summarising their respective qualifications and experience.

57. When addressing questions of fact and opinion, experts should keep the two separate. Experts must state those facts (whether assumed or otherwise) upon which their opinions are based; experts should have primary regard to their instructions. Experts must distinguish clearly between those facts that they know to be true and those facts which they assume.

58. Where there are material facts in dispute experts should express separate opinions on each hypothesis put forward. They should not express a view in favour of one or other disputed version of the facts unless, as a result of particular expertise and experience, they consider one set of facts as being improbable or less probable, in which case they may express that view and should give reasons for holding it.

RICS Surveyors acting as expert witnesses practice statement and guidance note

2.1 Your overriding duty as an expert witness is to the tribunal to which the expert evidence is given. This duty overrides any contractual duty to your client. Your duty to the tribunal is to set out the facts fully and give truthful, impartial and independent opinions, covering all relevant matters, whether or not they favour your client. This applies irrespective of whether or not the evidence is given either under oath or affirmation.

2.2 Special care must be taken to ensure that expert evidence is not biased towards those who are responsible for instructing or paying you.

2.3 Opinions should not be exaggerated or seek to obscure alternative views or other schools of thought, but should instead recognise and, where appropriate, address them. The duty endures for the whole assignment.

2.4 As an expert witness you must be able to show that you have full knowledge of the duties relating to the role of an expert witness when giving evidence.

f – Give details of any literature or other material which you have relied on in making the expert witness report, including the opinions of others

6.2 You may be invited to amend or expand an expert witness report to ensure accuracy, consistency, completeness, relevance and clarity. You must disregard any suggestions or alterations that do not accord with your true opinions, or distort them. a Where you change your opinion following a meeting of experts, a simple and dated addendum or memorandum to that effect should be prepared and issued. b Where you significantly alter your opinion, as a result of new evidence or because evidence on which you relied has become unreliable or for any other reason, you should amend your reports to reflect that fact. Amended expert witness reports should include reasons for amendments and in such circumstances those instructing expert witnesses should inform the other relevant parties as soon as possible of any change of opinion.

Your written report should ideally be presented in an organised, concise and referenced way, distinguishing (where possible) between matters of plain fact, observations upon those facts, and inferences drawn from them. It is recommended that you use plain language and, wherever use of technical terms is necessary, explain such terms to aid the understanding of the tribunal. It is advisable not to use words, terms and/or a form of presentation with the deliberate intention of limiting the ability of readers to check the correctness of any statement, calculation or opinion given. As regards your summary of conclusions, there may be circumstances where it would be beneficial to the tribunal to place a short summary at the start of the report while giving full conclusions at the end. The tribunal may find it easier to understand the flow of the report’s logic if an executive summary of the report has been provided at the outset.

RICS Practice Alert – February 2014

To comply with RICS’ mandatory professional statement and guidance, you must be able to answer ‘yes’ to all questions with absolute certainty.

a) Is the subject matter on which you have been invited to give expert testimony entirely within the scope of your personal professional expertise?

b) Is the expert witness report you will submit to the client entirely your own work? If not, have you clearly indicated the extent to which any content is not your personal work?

c) Have you undertaken the necessary inspections and investigations, and reported all relevant facts that are within your knowledge to back up all statements made in your report?

d) Are you confident that you can give an honest and rational justification for all opinions expressed in your report?

e) If you were cross-examined, could you substantiate each statement in your report with supporting facts?

f) Is your testimony prepared entirely to assist and inform the court/tribunal?

g) Could you say on oath that you have not been influenced by a personal desire, incentives or other pressures to present your instructing client’s case to the court/tribunal in the most favourable light as possible?

h) Are you satisfied that your report is scrupulously impartial?

If you or your firm have ever represented the client in a personal or professional capacity, are you certain that your report reflects your honest opinion and is not biased towards or against the instructing client?

j) Can you confirm that the basis of your remuneration (and that of your firm) is not related to the outcome of the court/tribunal proceedings?

k) Is the declaration at the foot of your report truthful in every respect?

l) If you have ever had your expert evidence rejected or criticised by a court/tribunal, can you provide a credible explanation to the present court/tribunal about why your current report should be considered reliable?

m) Have you complied with all the requirements for members set out in the current edition of RICS’ Surveyors acting as expert witnesses?

RICS Practice Alert – Acting as an expert witness in housing disrepair and other high-volume cases – April 2025

Examples of poor behaviours include the following:

- Experts being approached by claims managers requiring them to use pre-populated templates, standard schedules of charges or copy-paste reports without proper investigation and verification being undertaken.

- Claims managers or solicitors acting in high volume cases seeking to instruct the same expert in a large number of claims, creating a conflict of interest because of the amount of fees generated and the risk of losing revenue if the expert witness reports do not meet the expectations of those issuing the instructions.

- Information about the expert’s qualification or experience being misrepresented, either because of a reliance on templates, incorrect use of an RICS logo or because reports are altered after being submitted.

However, following Field v Leeds City Council [2000] 32 HLR 618, I struggle to see how this makes a report inadmissible. Defendant’s experts quite literally work for their own employer.

Common issues

- Not inspecting a room and then giving an opinion as to what might be there

- Not being strong enough in the language

- Not giving reasons as to why you disagree

- Not following PD 35

- Not being detailed enough

- Not including enough photographs

- Poorly structured and formatted

Criticism of one expert of another

Whilst this probably shouldn’t have happened, there is an example of one senior expert criticising the report of a junior expert. Points include:

- No reference to BRE and M3NHF rates

- Typographical errors

- No details of VP or relative humidity

- Consistency of evidence

- Incorrect reference to the law

- Ignored the allegations raised in the letter of claim

- Cracks in the Property – BRE guidance note 251

- A Part 35 response from C expert says he was using the meter in the pin-less mode, but the photographs attached to his report show him using it in the pin mode. The answer given shows that C expert is not familiar with how these types of meters are used

- A Part 35 response refers to equipment which was not mentioned at all in the original report, which contradicts another part of the report which reads ‘I have shown the sources of all information I have used’

- C’s report refers to the law in Wales throughout, when the Property was based in England

- C expert not a chartered surveyor

- C expert did not include a CV

- Para 5.4i says must distinguish between facts and assumptions. C expert has made statements about missing insulation on window reveals without actually checking

Conclusion

This is a long article which has condensed two hours’ worth of training.

I suspect we’re all going to get a lot busier come the end of October. I think it is worth remembering that we are all navigating the change in the law together, and at the centre of all of this are tenants that are sometimes living in dire situations.

The Part 35 expert plays a vital role in these cases. Ensuring the reports are of the highest quality will ultimately save costs and the Court’s time, as fewer of these cases would be taken to trial based on criticism of the expert’s report alone.

As always: this article is not to be construed as legal advice.

Jonathan McDonnell is a barrister at Park Square Chambers. This article first appeared on his blog, The Legal Position.

Must read

Fix it fast: How “Awaab’s Law” is forcing action in social housing

Housing management in practice: six challenges shaping the sector

Why AI must power the next wave of Social Housing delivery

Sponsored articles

Unlocking legal talent

Walker Morris supports Tower Hamlets Council in first known Remediation Contribution Order application issued by local authority

12-03-2026

16-03-2026 11:00 am