The COP26 Decision: The Glasgow Climate Pact

- Details

COP26 has ended with an agreement, currently Decision -/CMA.3, which will more snappily be known as the Glasgow Climate Pact. Estelle Dehon, who attended the first week of COP26, considers what was achieved, what was not achieved and what happens next.

What was achieved?

Transparency and the Paris Rulebook

There have been important successes achieved in Glasgow. The COP26 Decision represents agreement on what is known as the “Paris Rulebook”, which now sets a single transparency standard for how countries report on their emissions reductions under the Paris framework. That is crucial in allowing proper scrutiny of climate pledges and will ensure that, by 2024, countries’ actions can truly be compared and therefore scrutinised. That should allow more regular and more robust information on emissions reductions and on progress in implementing countries’ Nationally Determined Contributions (as the reduction commitments made under the Paris Agreement are known).

1.5 Degrees “Alive”

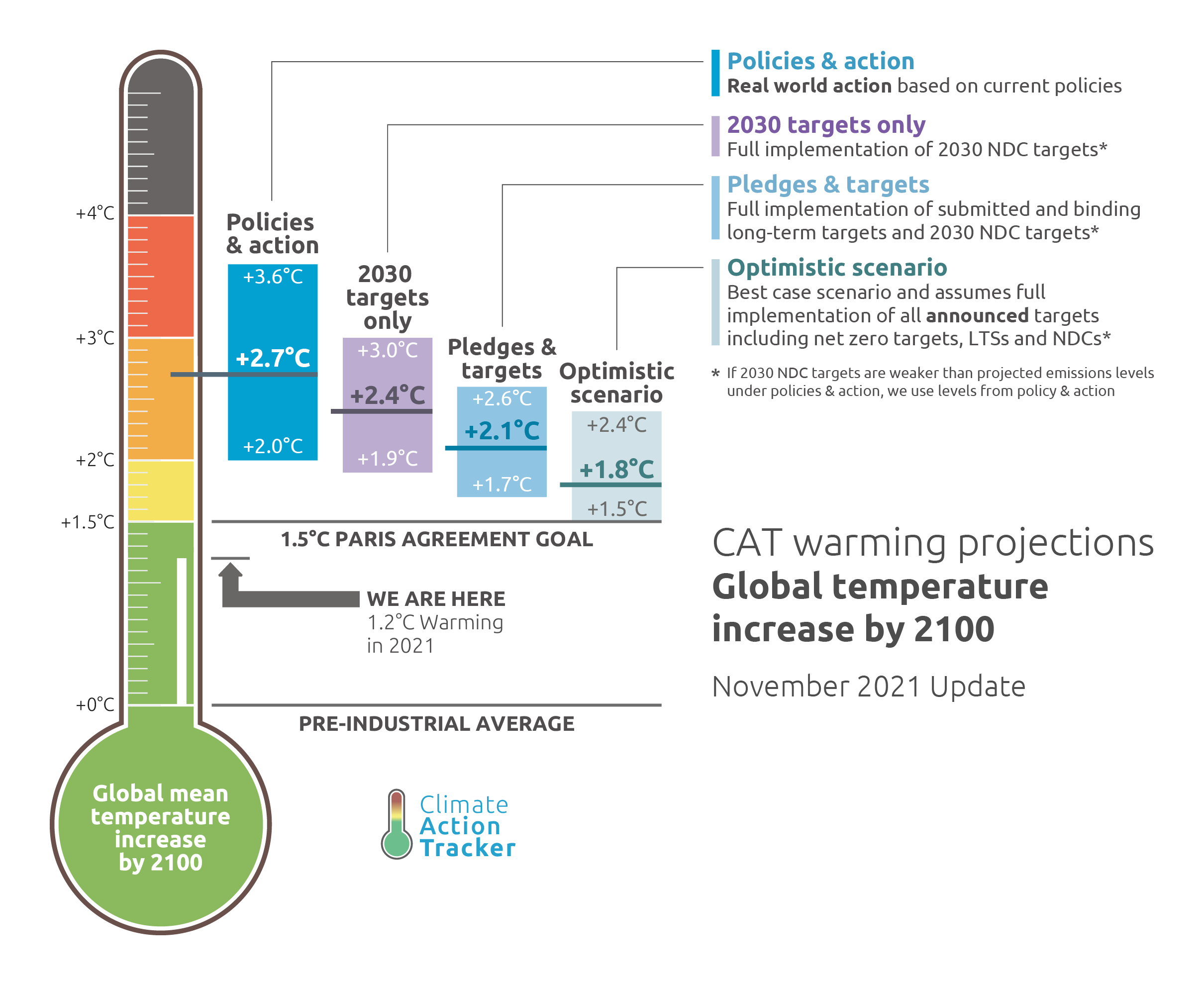

One of the most important goals of COP26 was to “keep 1.5 degrees alive” – to reach an agreement that means it is still feasible to keep global heating below 1.5 degrees C above pre-industrial levels by the end of the century. Alok Sharma, the COP President, told the closing session of the conference:

“We can now say with credibility that we have kept 1.5 degrees alive. But, its pulse is weak and it will only survive if we keep our promises and translate commitments into rapid action.”.

There will be a lot of debate as to whether 1.5 degrees is actually still alive. Crucial steps were taken: all major emitters are required to return in 12 months (rather than the longer five year period) to explain to the UN how their economy-wide policies and plans are aligned with the Paris temperature goals, and it is agreed that emissions must be cut by 45% by 2030 to align with 1.5 degrees.

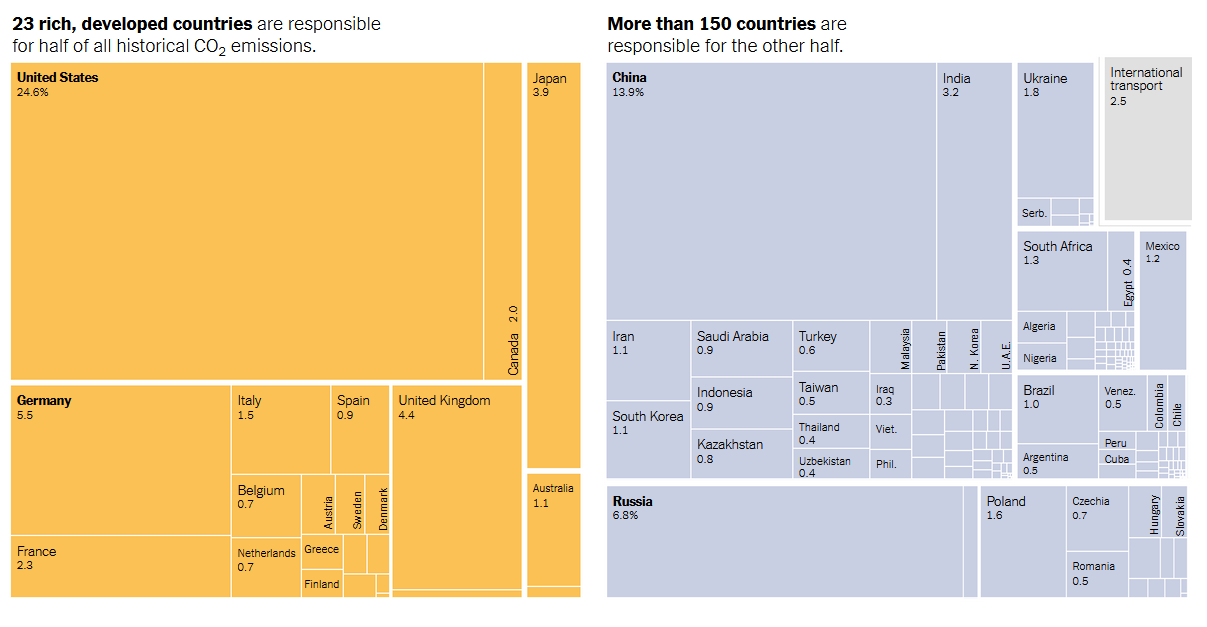

However, there remains a significant emissions gap. Climate Action Tracker calculated that global greenhouse gas emissions in 2030 will still be roughly twice as high as is needed to limit warming to 1.5 degrees and that the world is on track for 2.4 degrees of warming above pre-industrial levels by the end of the century.

Carbon Markets

The other big area of agreement was on carbon markets and carbon credits under Article 6 of the Paris Agreement, which has been an area of significant dispute and on which there was failure to agree at previous COPs. There was very significant concern that potential loopholes in these markets would allow countries an easy way to keep polluting. The COP26 decision does create unified and internationally controlled standards to avoid a situation where the same emissions reductions are claimed by multiple companies or countries and to combat fake emission reduction credits, either claiming as reduction something that would happen anyway, or taking credit for a reduction that was not driven by the money paid for the credit. But there are three big catches:

- There is already a carbon credit market, put in place under the Kyoto Protocol (the Clean Development Mechanism), which is widely agreed to be flawed with unverified credits, known as “zombie credits”. The COP26 Decision allows some credits from that market to be used in the new Article 6 markets – estimates differ, but between 100 and 300 million zombie credits may find their way into the new markets.

- It will be very difficult, at an international level, to ensure the integrity of the markets. Who will, for example, monitor whether the trees whose carbon-storing power has been sold in a credit are still standing or whether they have been victim to a forest fire?

- To work as a mechanism for driving down emissions, the credits need to reduce over time, otherwise the level of pollution remains the same. The COP26 Decision requires a mandatory 2% cancellation of each credit traded under the new centralised carbon market, but that is considered to be too low to contribute meaningfully to overall emission reduction. And mandatory partial cancellation does not apply to bilateral trades of emission credits, only voluntary cancellation.

What was not achieved?

That there was particularly symbolic wrangling over the name of the Decision. The vulnerable countries and the Climate Vulnerable Forum called for it to be the “Glasgow Climate Emergency Pact”, but the final agreed name edited out the “emergency”, so the “Glasgow Climate Pact” was announced. That editing out reflects a key criticism of the Decision – it fails to reflect the scope and urgency of the climate emergency and the actions required to address that emergency.

Climate Finance for Adaptation

The COP26 Decision notes the “deep regret” of developed countries for missing the $100 billion target of climate finance that should, under the Paris Agreement, have been provided to developing countries by 2020. It urges developed countries to “fully deliver” on that goal “urgently” though 2025. The requirement for the developed nations, who are most responsible for climate change because they have been emitting for much longer, to provide climate finance to developing nations was a key aspect of the Paris Agreement’s “common but differentiated responsibility”, which was central to the agreement being equitable.

The failure, by tens of billions of dollars, to meet the climate finance pledge very seriously damaged the credibility of developed countries and highlighted appalling inequality, where people in low-emitting climate vulnerable countries continue to die from climate related disasters, without the promised funding to adapt to climate change.

Loss and Damage

Increasingly, countries have recognised that there are some impacts of climate change that cannot be addressed or mitigated through adaptation – there is simply irrecoverable damage or loss. One of the big areas where progress was sought was therefore the establishment of a Loss and Damage Fund, separate from adaptation finance, which would operate as a type of “polluter pays” fund, requiring the most polluting developed countries to pay for loss and damage suffered by climate vulnerable countries. This is not an area addressed by the Paris Agreement, so the only way to bring such a mechanism into the set of international actions under the Paris Agreement was by establishing the fund via COP26. Scotland took a hugely symbolic step by being the first country to pledge money to a loss and damage fund: £2 million. However, the Loss and Damage Fund did not make it into the final Decision, with the US, UK and EU not being prepared to accept anything more concrete than further dialogue about loss and damage.

Fossil Fuels

For the first time since the Kyoto Protocol in 1997, the COP26 Decision specifically makes a pledge about fossil fuels. Initial draft text called on Parties to “accelerate the phasing-out of coal and subsidies for fossil fuels”. The final text:

“Calls upon Parties to accelerate the development, deployment and dissemination of technologies, and the adoption of policies, to transition towards low-emission energy systems, including by rapidly scaling up the deployment of clean power generation and energy efficiency measures, including accelerating efforts towards the phasedown of unabated coal power and phase-out of inefficient fossil fuel subsidies, while providing targeted support to the poorest and most vulnerable in line with national circumstances and recognizing the need for support towards a just transition.”

There was much debate about whether the text would remain in the decision at all. First "unabated" was added to the text about coal, and "coal power" was specified; then "inefficient" was added to the text about fossil fuel subsidies; finally, beyond the 11th hour, India and China secured the change from "phase out" to "phasedown". The result is many headlines blaming India and China for watering down the text. At one level, that is justified. At another, it is not – the problem with the text was that the US, EU and Australia pushed for a text that did not reflect common but differentiated responsibility and the reality of phasing out coal for developing (as opposed to developed) countries. The focus on phasing out coal (which is the fuel of choice for many poorer nations) without a similar stringent focus on phasing out oil and gas (the fuel choice for many wealthier nations), reinforced the distrust between developed and developing nations.

There is a significant risk that the narrative will be COP26 failed because of the single word-change by India and China, sweeping under the carpet the failures and risks around loss and damage, Article 6 loopholes, phase-out of oil and gas, and mitigation and finance gaps, driven primarily by failures on the part of developed countries.

What now?

COP26 will be celebrated as a success and branded a dismal failure. Lawyers and others fighting the climate crisis will pore over the text and take from it the best they can. The UK will come under increasing criticism for its failure to join the alliance of countries fixing a date to phase out oil and gas production (the Beyond Oil and Gas Alliance, led by Costa Rica and Denmark) and for the large number of oil and gas projects in the pipeline, including the proposed Cumbria Coal Mine, the Cambo Oil Field and the Surrey Oil development at Horse Hill. Climate campaigners will step up efforts, on the basis that the politicians failed in Glasgow and the resulting deal was inequitable. There is already a People’s COP26 Decision for Climate Justice. And the eyes of the world will begin to turn to Egypt and COP27 next year.

Estelle Dehon is a barrister at Cornerstone Barristers. She acted in the Cumbria Coal Mine inquiry (leading Rowan Clapp) and the legal challenge to the Surrey Oil development (led by Marc Willers QC; the appeal was heard by the Court of Appeal on 16-17 November 2021).

Must read

Sponsored articles

Unlocking legal talent

Walker Morris supports Tower Hamlets Council in first known Remediation Contribution Order application issued by local authority

Senior Solicitor - Property

Legal Officer

Locums

Poll

21-04-2026

01-07-2026 11:00 am