A zero sum game?

- Details

The number of SEND tribunal cases is rising and the proportion of appeals ‘lost’ by local authorities is at a record high. Lottie Winson talks to education lawyers to understand the reasons why, and sets out the results of Local Government Lawyer’s exclusive survey.

According to research by analysts Pro Bono Economics, councils spent nearly £60 million in 2022 on unsuccessful court disputes in the SEND tribunal, fighting claims brought by parents and carers seeking support for children and young people with special educational needs and disabilities.

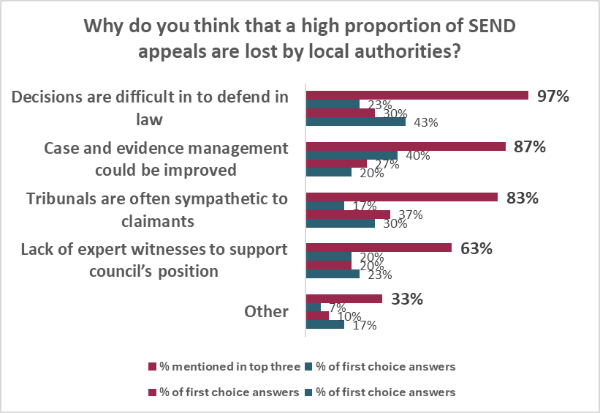

The ‘success’ rates for councils were shockingly low. In 2021-22, 96% of SEND tribunal appeals were upheld at least in part in favour of the appellant, while in the academic year 2022-23, HM Courts and Tribunals Service recorded 14,000 registered appeals, an annual increase of 24%.

With mounting tensions between local authorities and people seeking support, Local Government Lawyer conducted a survey of education lawyers to consider where the responsibility lies, and what solutions might be available. Forty-two lawyers, both in-house and claimant, took part.

Issues Under Appeal

Issues Under Appeal

Looking at registered appeals by type for 2022-23, 28% were against the council’s ‘refusal to secure an Education, Health and Care Plan (EHCP) assessment’, while a total of 58% were in relation to the content of EHC plans.

EHCPs combine a child’s education, health and social care support into a legal document issued by local authorities in England. Parents can appeal against council refusals to assess a child’s needs or to issue an EHCP. Disputes can also arise over the contents of a plan, for instance, if the school suggested by the council is not deemed appropriate by parents. In 2022, for the first time, fewer than half of all EHCPs were issued within the statutory 20-week timeframe.

“Growing culture of non-compliance”

IPSEA, (the Independent Provider of Special Education Advice), a charity which supports the parents of SEND children, has argued that one of the only ways in which local authorities can reduce the amount of ‘lost’ SEND appeals is if they comply with the legal framework and make lawful decisions.

Speaking to Local Government Lawyer on the “exponential” growth of appeals, Ali Fiddy, Chief Executive of IPSEA, blames unlawful decision making by local authorities. She says: “We need to move away from the idea that the system is littered with disputes about special educational provision. Actually, the system is littered with unlawful decisions.

“This is not parents and carers who are seeking to achieve the gold standard for their child. They are seeking to achieve basic entitlement, what the law requires.”

This opinion was echoed by a number of claimant lawyer respondents. One wrote: “There is a growing sense that public bodies are seeking to deflect from the epidemic of unlawful decision-making taking place, by suggesting the high number of appeals is driven by unrealistic expectations of parents and young people.

“The situation is that the Tribunal applies the law to the facts, and finds overwhelmingly that LAs have not applied the correct legal test and failed to comply with their legal duties.”

Research conducted by the pro bono panel of the Administrative Justice Council (AJC) suggests that local authorities are responsible for a “significant” part of the problem. Using survey data provided by 12 SEND tribunal judges over a period of six weeks, the study identified that, in the opinion of the judge, there were “significant flaws” with either the initial decision itself or the local authority’s subsequent participation in the appeal in 50% of cases.

Delaying the process

There is a growing perception amongst parents and their advisers that local authorities are purposely delaying assessments and provision as a money saving tactic. One survey respondent claims that it is “more cost effective” for councils to see if a parent will submit an appeal and wait approximately a year before being ordered by the Tribunal to assess needs, issue a EHC plan, and put in place specific provision.

Speaking to Local Government Lawyer, the Local Government and Social Care Assistant Ombudsman, Richard Bailey, warns that councils are “not respecting the timelines”, and this delay is causing an adverse effect on children. “Parents often have to step in during the interim to put provision in place at their own cost”, he adds.

Sarah Woosey, specialist education lawyer at Simpson Millar, argues that delaying provision for young people can, in reality, lead to their needs becoming more costly – a larger expense for councils in the long run. She says: “A big issue from the parent’s perspective is that local authorities can save money by delaying appeals, so there’s a perception on the parent’s part that this system favours councils, because it allows them to save money in terms of paying for the provision. On the swing side, when [councils] get to the tribunal and lose, they have to pay for the provision anyway.

“The negative side of delaying this type of provision for young people is that their needs are not static, so the longer they go without additional support, in lots of those cases those needs will become more costly.”

She adds: “The way to save this money is by addressing the issues early and looking at them when first raised.”

One lawyer respondent suggested that the statutory 20-week timeframe for issuing EHCPs has become “unreasonable”, given the duty for local authorities to consider parental preference. Another said that although it would benefit parents if the system worked more quickly, the most impactful change would involve local authorities “reviewing their approach to decision making, and preventing the need for an appeal in the first place.”

Funding pressures

Funding pressures

Something that claimant lawyers, local authorities and parents can all agree on is the SEND system is severely under-resourced. Councils tend to say that mainstream schools can’t meet the needs of many children due to a lack of funding and resources from Government, which leads to parents seeking more support.

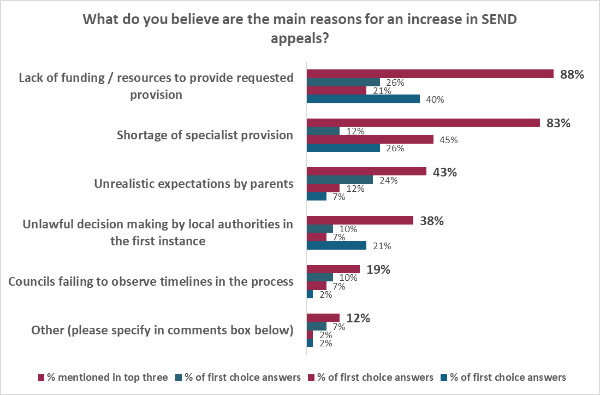

According to the survey, readers selected ‘Lack of funding / resources to provide requested provision’ as the most important factor for an increase in SEND appeals, followed by ‘unlawful decision making by local authorities in the first instance’, and ‘shortage of specialist provision’.

Some respondents called for a clearer understanding by tribunals of the financial pressures which local authorities operate under, which inevitably affect decision making. One described a “fundamental disconnect” between the legal position and the reality of resource available.

However, councils cannot use 'lack of resources' as a reason in court for not providing provision. Section 42 of the Children and Families Act 2014 provides that local authorities have an absolute duty to make any provision specified in an Education, Health and Care Plan.

Local authorities can, though, decline to name a school of parental preference if it would amount to “an inefficient use of resources” or “unreasonable public expenditure”. For example, if parents would like their child to attend a particular school, but the council has identified a cheaper alternative they consider could meet the child’s needs, the local authority might rely on this argument.

Councils have noted that although the present system puts parental choice at its heart, local authorities frequently do not have the budget to execute this.

Fuelling the fire

It should be noted that an appellant only needs to achieve one amendment, which may not have been requested prior to appeal, for the SEND appeal to be recorded as a ‘successful’ outcome by HM Courts and Tribunals. Therefore, the concept of ‘winning’ and ‘losing’ isn’t black and white.

Questioning the ‘bad’ local authority narrative, Laura Thompson, Senior Associate at Browne Jacobson, says: “I don’t think that putting out the statistic [that over 90% of cases are upheld in favour of the appellant] is particularly helpful, in terms of parents’ faith in the system. Not all local authorities ‘behave badly’, and some of the recorded ‘losses’ are because local authorities have agreed to what parents want following receipt of evidence information that wasn’t available before the appeal was lodged.”

One survey respondent observed that tribunals can use very harsh language when talking about a local authority, which can break down the relationship between parent and local authority, causing more distrust. One claimed that tribunals are “set up for local authorities to fail” and called for an overhaul of the system.

“The tribunal process in its current form doesn't help anyone and lazily points the finger of blame at local authorities who are the easy pantomime villain. The narrative needs to change dramatically,” said another.

Laura Thompson observes a greater awareness of parents’ ability to appeal to the tribunal. She notes that the increase in SEND appeals could be partially attributed to more support and advice available to parents, alongside the core issues of a lack of special school places and resources.

Next steps

With almost £60 million of public funds being spent on ‘unsuccessful’ court disputes, and a growing demand for EHCPs putting further pressure on a system already in crisis; it is clear that something needs to change.

Sarah Woosey argues that policy change will not address the current problems. She says: “The legal duties to ensure children are in suitable school places are there already – but without funding and money to create those places, this is the reason for a large number of disputes at the moment”.

She questions whether the government should look at the cost jurisdiction of the SEND tribunal. She says: “At the moment, it is a no cost jurisdiction, so even when LA’s lose, they don’t have to pay the legal costs of the successful party.

“If the government were to change that, would local authorities be forced into dealing with these issues at an earlier stage and in a more efficient way?”

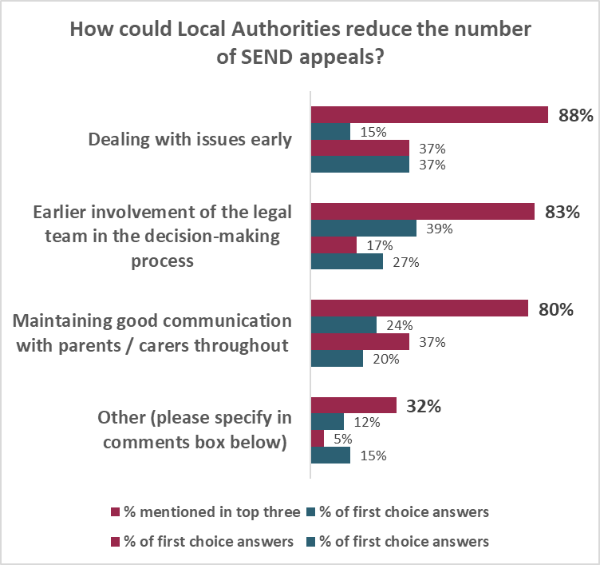

Asked how local authorities could reduce the number of SEND appeals, a number of survey respondents recommended a stronger use of mediation, more pro-active case management from the tribunal at an early stage, and training on SEND law within local authorities, so they can ensure their decisions are legally compliant from the beginning.

One suggested there should be “active case management to weed out weak claims, rather than giving the parent the benefit of the doubt at all times”, and there should be an opportunity for observation of hearings “to improve learning and increase transparency”.

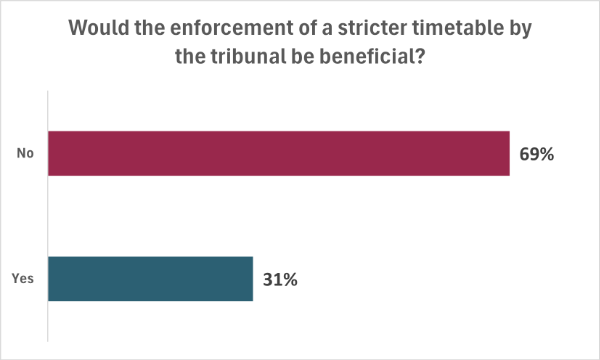

Asked whether the enforcement of a stricter timetable by the tribunal would be beneficial, the majority (69%) of survey respondents said no. The general consensus was that resources are already stretched, and this could compound an already struggling system.

Assistant Ombudsman Richard Bailey highlights the importance of maintaining good lines of communication with parents, and making decisions in the best interests of the child, rather than based on financial factors.

Despite playing a separate, distinct role from the SEND tribunal, the Local Government and Social Care Ombudsman (LGSCO) has the power to investigate complaints against councils made by parents of children with SEND. If fault is found, the Ombudsman makes recommendations for the council to remedy the injustice, often in the form of financial compensation and an apology.

Considering the viability of the LGSCO as an alternative to the SEND tribunal, there are situations in which a parent might turn to the Ombudsman, for instance, if the local authority does not provide home-to-school transport that a child is legally entitled to, or if the local authority fails to comply with legal deadlines to complete a EHC needs assessment, resulting in the child missing out on special educational provision or schooling.

However, the Ombudsman’s jurisdiction doesn’t enable it to look at what is happening in schools. Richard Bailey said: “If we had the power to investigate what’s happening in schools, we might be able to get resolutions sooner for parents and children, and deflect these cases down the line from becoming extensive complaints or appeals which they can grow into.”

The Ombudsman noted that if it feels someone should appeal to the Tribunal, it will say so, and will not be able to investigate the complaint.

Improvement plans

The number of applications for EHCPs are growing year on year. During 2022, there were 114,482 initial requests for a plan, up from 93,300 in 2021. As of January 2023, the number of children with EHC plans increased nationally to 517,000, up by 9% from the previous year. As highlighted by education lawyers, the Covid-19 pandemic created an explosion of demand for special educational provision.

On 2nd March 2023, the Department for Education (DfE) published its SEND and Alternative Provision (AP) Improvement Plan. The DfE said the transformation of the system would be underpinned by new national SEND and AP standards, and strengthened mediation between parents and local authorities before cases go to tribunal. However, the Local Government Association (LGA) claimed that the measures do not go far enough to address “fundamental” cost and demand issues.

While many issues are therefore set to remain, smaller scale solutions such as SEND law training, effective mediation, and an earlier involvement of the legal team in the decision-making process could be considered. Lastly, it might be time to question the “pantomime villain” local authority narrative, or equally damaging “pushy parent” stereotype, both of which only create further divisions and distrust. As said by IPSEA, parents and carers are not seeking to achieve the “gold standard” for their child. They are seeking to achieve basic entitlement, which every child or young person with SEND deserves.

Lottie Winson is a reporter at Local Government Lawyer