Time for change

- Details

The President of the Family Division has demanded that the vast majority of childcare proceedings are concluded within the statutory 26-week deadline. Lottie Winson analyses the results of Local Government Lawyer’s exclusive research to see whether Sir Andrew is likely to get his wish.

|

To view or download this article in pdf form please click here |

According to Cafcass, there are approximately 5,100 children in public law proceedings waiting longer than 52 weeks for a decision, and of those, close to 850 are waiting more than 100 weeks.

In November, the President of the Family Division, Sir Andrew McFarlane, lost his patience. In his regular ‘View from The President’s Chambers’, he told all involved in public law children cases that ‘delay has become normalised’, and that there needs to be a ‘radical change of culture within the family court’.

He reiterated the need for practitioners to “reconnect with the core principles of the Public Law Outline”, to ensure that the statutory requirement of completing each case within 26 weeks is met once again. He instructed that in all new cases, there will be an expectation that judges will approach them by “rigorously applying the PLO”.

Outlining reasons for everyone in the system to go back to operating the PLO “in full and without exception”, Sir Andrew McFarlane said: “Taking no action involves accepting that things will remain as they are. Indeed, for the reasons that I have given, the normalisation of delay creates something of a downward spiral in which the situation simply gets worse rather than better.”

Whilst shifting gear and working to a tighter procedural template will initially require effort and cause difficulties, he added, “if the result is that in most courts and for most children the outcome is positive, and that, thereby, frees up resources to address new cases in a more timely way, then that is a ‘win-win’ outcome.” The experience, he said, of those court centres which had already followed this course was very positive.

To overcome the perceived unacceptable level of delay in the system, Sir Andrew McFarlane and Mr Justice Keehan outlined a 20-point plan for family practitioners to follow in all cases from 16th January (see dropdown below).

1. The Public Law Working Group’s recommendations should be followed in all cases

2. Assessments carried out ‘pre-proceedings’ are to stand as evidence in care proceedings and are not to be repeated

3. Timelines in the ‘public law outline’ should be adhered to, so the case management hearing (CMH) should be listed before day 18

4. Urgent applications prior to the CMH should only be listed in ‘genuinely urgent’ cases. It will be for the Court to determine if the matter is urgent

5. Any urgent hearing should not delay the case management hearing

6. The Gatekeeping order must be complied with, including for example, the parents’ responses to threshold to be filed and served so that their case is understood in advance of the CMH

7. Updating assessments need to be focussed

8. Part 25 applications should be filed and served before the case management hearing and there needs to be ‘stringent application of the necessity test’

9. Every hearing must be effective and be the subject of robust case management

10. In all cases at a CMH the case must be timetabled to an issues resolution hearing (IRH) – (only in exceptional cases should a final hearing be listed at CMH or prior to the IRH)

11. Split hearings cause delay. Should be reserved for single issue cases

12. Only list a further case management hearing (FCMH) if necessary

13. Non-compliance must be notified by any party

14. Urgent non-compliance will be listed

15. Parents and carers must be given a clear date by which they must identify any potential alternate carers and they must be informed that any alternate carers put forward after that date are most unlikely to be assessed because of the resulting “harmful delay in the planning of the child's future”

16. Robust case management at issues resolution hearings - rarely should the court accept that the case is said to be contested. Waiting for a contested final hearing (FH) is “not welfare neutral for the child”

17. Narrow disputed issues should be dealt with on submissions at issues resolution hearings

18. Expert witness attendance must be justified (permission is required to call on an expert witness – question is it ‘necessary and proportionate’?)

19. Cases should conclude within 26 weeks. The principal aims are to have no more than 2 or 3 hearings per care proceedings

20. District Judges should agree assessment timetables

To gain an insight into the experiences of child protection lawyers and their views on the proposed changes, Local Government Lawyer conducted a survey to assess their viability in practice, in which 41 local authority child protection lawyers took part.

The aim of the survey was to uncover where delays are occurring in the process, to analyse whether the 20-point plan instructed by the President can address them, or if the issues are more deeply rooted within the system.

The survey also observed the attitudes of practitioners towards the practice directions, to see whether the changes are welcome, or seen as an added burden on an already struggling workforce.

The key question is: can the family court make its way back to the 26-week requirement, or is the notion of a “radical reset” slightly too radical, considering the resources available?

The survey found that despite most of the new measures being ‘achievable’, over half of respondents (60%) said that the 26 week target for a case to conclude would be either “quite” or “very” difficult to achieve, demonstrating that the problems in the system may go deeper than tweaks to the procedure rules can solve.

Delays at all stages

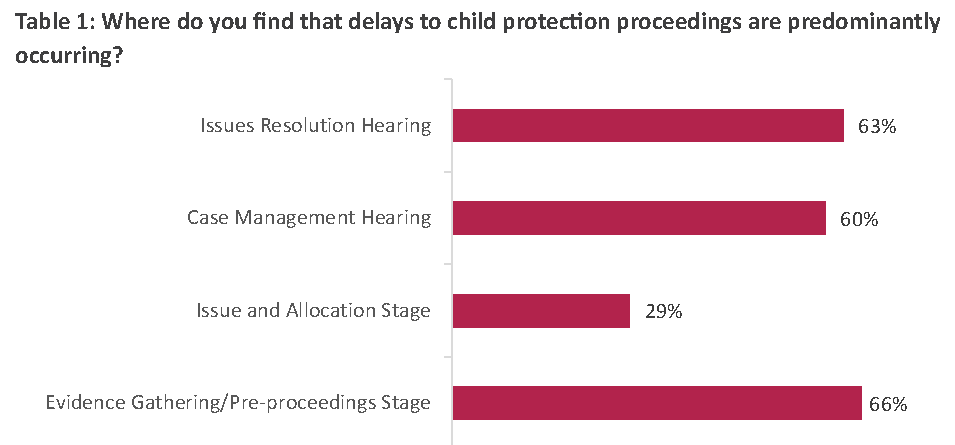

Asked where the delays to child protection proceedings were predominantly occurring (see table 1), respondents noted delays across all stages, with the ‘Evidence gathering / Preproceedings stage’, the ‘Case Management Hearing’ and the ‘Issues Resolution Hearing’ being seen as having the highest number of delays.

Key reasons for delay outlined by the survey respondents in the pre -proceedings stage included high staff turnover of social workers due to large caseloads and “pressure of work”, causing delays in issue documentation and assessments. Other respondents outlined poor engagement with the pre-proceedings process, with examples including delays in parents providing evidence, and kinship assessments, experts and carers being put forward late. One respondent said that “pre-proceedings matters are not prioritised due to court matters taking precedence.”

Some survey respondents told us that delays in providing Guardians can contribute to a longer process. One child protection lawyer said: “Children’s Guardians have almost never completed an analysis prior to the first hearing, and will often not have seen the child.”

When asked if anything is being done to limit delays within this area, Jack Cordery, Director of Operations at Cafcass, said that under the re-launch of the Public Law Outline, Cafcass is working with the Department for Education to pilot a local authority facilitated meeting between the child’s guardian and the social worker, aimed at making the “first and every hearing count”.

He said: “An average of 68% of care proceedings are short notice applications, which does not give the Guardian sufficient time to read and analyse the volume and complexity of the submissions to provide a meaningful initial analysis at the first Case Management Hearing. The same is true for seeing the child before the first hearing.”

Alongside the pilot, he announced that Cafcass is also committed to establishing a timetable that is in the best interests of the child in advance of the first case management hearing, which also has the intention of 26 weeks.

At the Case Management Hearing (CMH) stage of the PLO, a number of respondents outlined the prevalence of delays in listing a CMH, and hearings being cancelled last minute. One survey respondent said that parenting assessments that have been completed during pre-proceedings are “rarely accepted”, and a further assessment is therefore directed, causing a repetition of work and further delays. It was said by another that parents sometimes decide to put forward carers at CMH stage, “despite having time at pre-proceedings to do so”.

Joy Brereton, specialist children barrister at 4 Paper Buildings, said that during the pandemic, “things started to slip, and habits were created which have now remained”. She said: “If people turned up at the first case management hearing and experts weren’t available, or parents hadn’t filed a response to the threshold, it was just adjourned for a further case management hearing.”

At Issues Resolution Hearings (IRH), the key areas of delay were said to be caused by long court wait times for IRH dates, waiting for assessments or challenge by relatives, inappropriate use of experts and lack of judicial availability. One child protection lawyer observed the court’s “unwillingness” to make a decision at IRH stage, despite there being “overwhelming evidence to do so”.

Other respondents noted that counsel and parties often seek evidence on issues that will not effect the final orders made. One said: “Too many cases get off track when parties wish to litigate matters that are irrelevant to ultimate conclusion. Judges must be enabled to make the clear decisions in front of them at the earliest time.”

Commenting on the child protection proceedings process as a whole, a child protection lawyer said: “Delays are occurring throughout the whole process. There are huge delays with the court – waiting months for final hearings. Local authority legal and social care departments are under resourced with high turnovers of staff. None of this is helped by added pressure coming from the court with unrealistic timescales. [It is] a very toxic environment to work in currently.”

20 questions

When asked how realistic the 20 bullet point measures outlined at the PLO launch event would be to achieve in practice, for the majority of points, over 70% of the survey respondents said they would either be ‘easily achievable’ or ‘mostly achievable’.

However, concerns were expressed in relation to:

• ‘Assessments carried out ‘pre proceedings’ are to stand as evidence in care proceedings and are not to be repeated’ - 37% said this would be ‘quite’ or ‘very’ difficult to achieve.

• ‘Part 25 applications should be listed before the case management hearing and there needs to be ‘stringent’ application of the necessity test’ - 31% said this would be ‘quite’ or ‘very’ difficult to achieve.

• ‘Parents and carers must be given a clear date by which they must identify any potential carers’ - 37% said this would be ‘quite’ or ‘very’ difficult to achieve.

• ‘Designated family judges should seek to agree timelines for the assessment of parents in the proceedings’ - 31% said this would be ‘quite’ or ‘very’ difficult to achieve.

The most difficult measure to achieve according to our survey was: ‘Robust case management of the IRH to avoid stress & delay for children & parents. Rarely should the court simply accept that the case is said to be contested’.

Only 43% of respondents said it would be ‘easily achievable’ or ‘mostly achievable’, with 43% saying it would be ‘quite difficult to achieve’ and 14% saying it would be ‘very difficult to achieve.’

The President of the Family Division said that waiting for a contested final hearing (FH) is not “welfare neutral for the child”, adding that the parties should expect the court to give “firm judicial indications (with the usual caveats).”

Commenting on why this measure might have been deemed difficult to achieve by survey respondents, Somia Siddiq, a Children Panel solicitor and Co-Chair of the Association of Lawyers for Children (ALC) said: “I agree that this is challenging to achieve particularly when the care plan is permanent placement outside of the family. Parents clearly have the right to challenge evidence and doing so within the court process is the only way.”

She explained that the President’s reference to the ‘usual caveats’ most likely refers to any decision being Article 6 and Article 8 compliant and ensuring welfare “remains paramount”.

On the point: ‘Expert witness evidence must be justified’, outlined by Mr Justice Keehan, Joy Brereton shares some concern over how the courts are going to deal with whether or not an expert can be cross examined.

She says: “If there’s an unfairness, one thing I know lawyers and particularly barristers are unsure about is, if they are using an expert and don’t agree with their views, why shouldn’t they be able to cross examine that expert on behalf of their client?”

On the issue of cross examination, Emma Roberts, a barrister at Albion Chambers described this as “a change in process, but not an insurmountable one.” She added that if the ability to cross examine is going to be much more focussed, the written questions are going to have to be “considered very carefully”.

There were also mixed opinions from organisations within the child protection sector on whether achieving the 26 week deadline would be beneficial in all circumstances.

Children’s welfare charity, CoramBAAF, said it is in support of a return to a 26-week timeframe, when this is achievable, as it “secures timely decision making for children and their families”. However, it argued there are instances where “delay is necessary”, adding that delay caused by necessary assessments of prospective kinship carers or interim placement of a child with a proposed special guardian is both “planned and purposeful delay”.

Emma Roberts observes that some local authorities seek no less than 16 weeks for kinship assessments. In light of the new timescales outlined by the President, she said: “I think they’re going to have to be told they can’t have it.”

She added: “It’s going to rely on refocus and re-organisation in local authority teams, to make them realise they don’t have the luxury of that [16-week assessment].” She continued: “It’s one of the last bastions of those luxury timescales.”

Commenting on the 26-week deadline, Cafcass noted that while not every set of proceedings can be concluded within 26 weeks, it is “necessary to start with that intention".

“There are wide variations in the duration of proceedings around the country which must be addressed by us all," Jack Cordery of Cafcass says. "There are some areas, for instance, where the average duration in public law proceedings is already close to 26 weeks and others where it is much longer. As a system, we were closer to 26 weeks prior to the pandemic. So, we know it is achievable.”

Long Covid

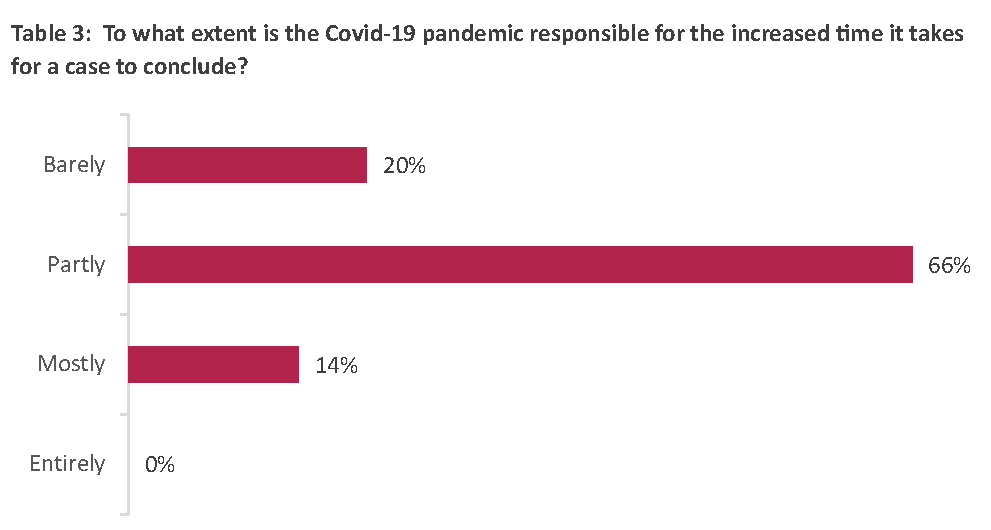

In order to assess how much of an impact the Covid-19 pandemic had on the ‘normalisation of delay’ within public law proceedings, we asked survey respondents to outline the extent to which the pandemic was responsible for the increased time it takes for a case to conclude. In response, over 60% of child protection lawyers said it was only ‘partly’ to blame, and cited other factors with an equal or greater impact. (See table 3)

One respondent noted that there were extant issues pre-pandemic, which have been “brought to the fore” by Covid. Some even pointed to benefits to the process brought about by Covid, such as remote hearings allowing for hearings to be listed sooner. Remote hearings have been a “positive implementation for non-contentious hearings” and freeing up social worker time, said one respondent.

The general consensus was that although the pandemic had an impact on factors such as the court’s capacity, these issues have mostly been resolved. However, it was said that notwithstanding Covid, it is still “extremely difficult” in many instances to conclude cases on time.

A number of respondents said that rather than the pandemic, the key reason for extended time is due to poor availability and retention of social workers and advocates in public law proceedings, with one describing the social care system as being at “breaking point”.

One lawyer outlined an example of a case they have been running since July, of which they are onto the fifth social worker and third team manager. They said that “overworked” social work teams are struggling to complete the written work required for court proceedings, which impacts the rest of the process.

So how those in the Child Protection sector view the practice directions as a whole? There are contrasting views on whether the new measures are welcomed.

Many feel that the new measures will simply add extra weight on an already overburdened and “chronically underfunded” sector. One lawyer commented: “I agree with the aims of the PLO but there is no recognition of the reality of the situation on the ground. Implementing this now, with all of the other changes also being forced through is just about the final nail in the coffin and indicative of the lack of respect the judiciary have for those actually doing child protection”.

For many of the reasons for delay cited by lawyers, the solutions outlined by the judiciary are far from the whole answer. The issues created by under-resourced departments and high turnover of social workers and lawyers will arguably require more fundamental change at a structural level.

Despite universal agreement that change is necessary, for the benefit of children and young people, there is uncertainty around whether approaching cases by “rigorously applying the PLO” will be enough to achieve the change required.

Lottie Winson is a reporter at Local Government Lawyer.