- Details

Bridging the gap

The Legal Department of the Future survey reveals that local government legal teams are employing a range of strategies as they face up to a challenging combination of increased workloads and severe pressure on resources. Philip Hoult reports.

What are the main challenges facing local government legal departments? What strategies are heads of legal and their senior management teams employing in response? Are departments being scaled back, left as they are or even expanded? What scope is there for further growth in the number of shared services? And is the sale of legal services to other public bodies central to teams securing their long-term prosperity?

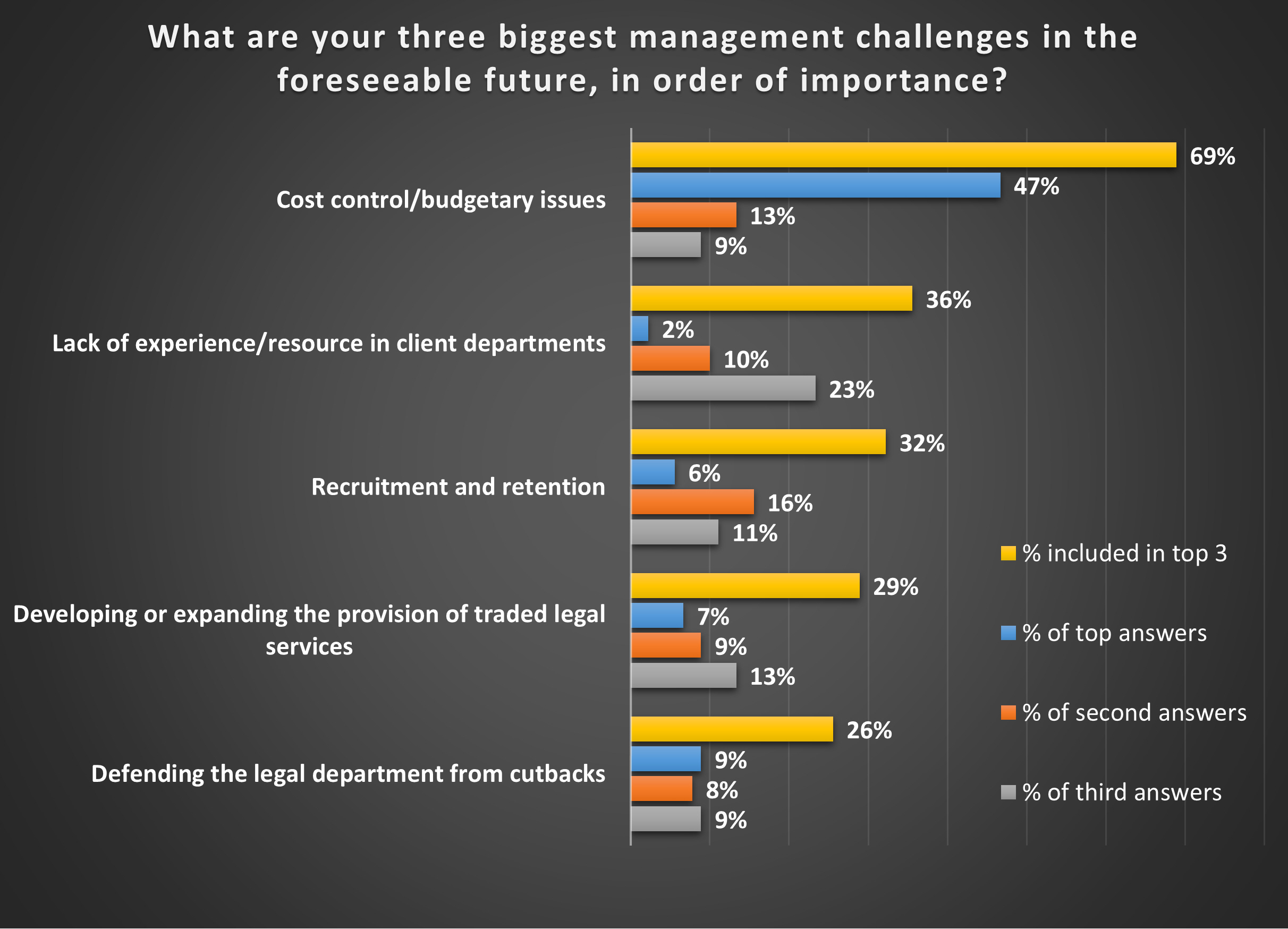

The Legal Department of the Future survey of 100 heads of legal sought to find answers to these and other important questions. As in the previous four editions of our research, we asked respondents to identify their top three management challenges from a list of 14 criteria.

You might be forgiven for expecting there to be little change from the 2012 survey – after all the financial environment faced by councils has remained bleak – and it is true that ‘cost control/budgetary issues’ are still considered the single biggest management challenge, included by 69% of heads of legal in their top three.

However, after that it is all change. Constitutional and corporate governance issues were in second place in the last survey but have now fallen away. Heads of legal instead point to a lack of experience and resource in client departments as their second most significant challenge (included by 36% of heads of legal in their top three).

What this can mean in practice is that less experienced officers seek reassurance more frequently from the legal team before taking decisions, adding to the department’s workload. Or they fail to obtain legal input in situations when they should do, leading to wrong decisions being taken and greater legal risk for the local authority.

The third most significant challenge – the difficulties in recruiting and retaining lawyers – has also shot up the list, included by 32% of heads of legal in their top three. This reflects the fact that three years ago the private sector was just coming out of the other side of the recession; now it is buoyant, particularly when it comes to recruiting in-demand areas of property, planning and regeneration. (For a discussion of careers issues, including how local authority legal teams can compete in this environment, see pages 36-45 and also the summary of our roundtable of heads of legal on pages 16-22)

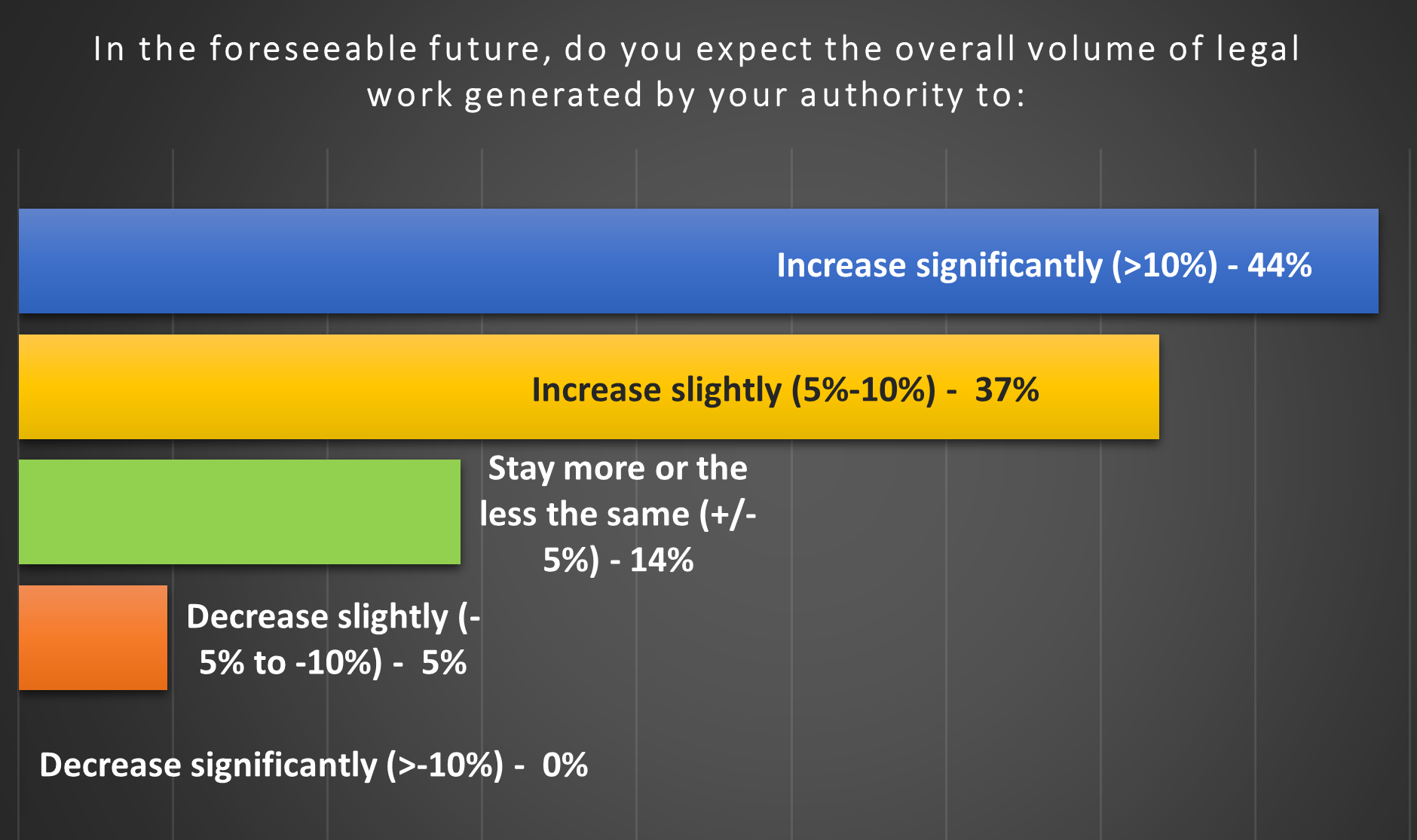

We went on to ask respondents whether demand for legal advice was set to grow, fall or stay the same in the foreseeable future. Some 44% expect the overall volume of work to increase ‘significantly’ (i.e by 10% or more), up from 37% in 2012. A further third (37%) expect demand to increase ‘slightly’ (by 5-10%), meaning that, overall, four in five heads of legal (81%) expect an increased workload. As few as 5% of respondents predict a decrease.

What are the reasons for this? The survey suggests that there is no single factor at play but several. On the positive side there has been a return of regeneration, projects and property work aimed at boosting economic growth in local communities.

“There has been an upturn in the economy and the council needs to become financially self-sufficient, leading to more commercial projects,” says one head of legal. As you would expect with a growing economy, there has been a rise in the number of planning applications, leading to an increase in inquiries and Planning Court hearings.

Heads of legal also point to the work generated by local authorities having to respond to their financial predicament. This has translated into restructurings, service closures, outsourcing, shared services, asset sales and a greater interest in income generation. A number of respondents highlight the intention of their authorities to become commissioners of services rather than direct providers.

Then you have to throw into the mix factors affecting individual practice areas such as children’s and adult social services. The Care Act 2014 and the Supreme Court ruling in the Cheshire West case on deprivations of liberty – both genuinely landmark developments – are still being felt by all those authorities with responsibility for adult care.

In children’s services, reforms aimed at ensuring that the majority of care proceedings complete within a 26-week period have had the effect of front-loading legal work. The number of care applications received by Cafcass has continued to rise relentlessly, with the total for the first half of 2015/16 pointing towards yet another record year.

Levels of litigation remain high as well, particularly in relation to judicial review proceedings as claimants seek to challenge the implementation of cuts to services. A number of local authorities have faced legal actions as they seek to shake up their provision of library services, for example.

So what can legal teams – and those responsible for managing them – do to tackle this conundrum? We asked heads of legal about the following strategic options:

● Changing legal department sizes and structures;

● Getting the most out of the authority’s external legal spend;

● Implementing shared services;

● Setting up alternative business structures;

● Generating extra revenue by selling legal services; and

● Partnering with the private sector.

Going for growth

Against a backdrop of further cuts to local authority budgets, you might think that the vast majority of legal departments would be shrinking in size. But the survey found that almost exactly the same percentage of heads of legal (32%) expect their teams to increase either slightly or significantly in size as expect them to stay more or less the same (35%) or decrease slightly or significantly (31%).

Pursuing a growth agenda for a legal department at this time can be difficult, however. One respondent notes that there is “no political or management appetite for more lawyers” in their authority and that “lawyers are seen as blockers not enablers, despite our best efforts”. For others, though, the equation is simple – “more work undertaken in-house means more lawyers required”.

One head of legal cautions that “extra posts will need to more than pay for themselves in extra income or saved external costs”, while another suggests that any growth in the number of lawyers will be for a fixed term, to help the council deliver its agenda. “Beyond that, we are likely to have to bear the same level of cuts as other parts of the organisation,” they say.

There is, of course, the previously mentioned challenge of filling posts in the most in-demand practice areas, which heads of legal suggest are currently procurement/contracts, planning, property and child protection. How can legal departments compete with private sector firms in some of these areas for the best talent? “Pay rates available in local authorities mean we struggle to recruit in contracts/commercial property teams,” acknowledges one head of legal. “T&Cs in local authorities have stagnated in the recession and are now unappealing,” adds another. “We need to do something to change this.” The cutbacks to trainee posts during the recession are also said to have had a negative impact.

Are fixed-term contracts, which an increasing number of authorities appear to be offering, part of the problem too, particularly if there is no significant financial upside to compensate for the greater uncertainty? One head of legal acknowledges that these deals are unpopular with candidates. This view is backed up by our experience of operating the Local Government Lawyer jobs board for the past six years, where fixed-term vacancies attract significantly fewer views and applications than those offered on a permanent basis.

In good shape?

The ability to reshape a legal department is a key part of the toolkit available to senior management, whether the team is set to increase or reduce in size. In this respect more than a third of heads of legal (37%) expect to use fewer locum solicitors and barristers going forward – perhaps through the recruitment of additional permanent staff or the provision of extra capacity via shared service arrangements. This is almost double the number of respondents (19%) who expect to use this pool of lawyers to a greater extent in the foreseeable future.

Growth in staff numbers, where it is happening, meanwhile looks set to be at junior levels. Almost half of heads of legal (48%) say they expect their numbers of paralegals to grow, compared to 19% who expect them to fall. Similarly, 32% predict that their cohort of assistant solicitors will increase, while 23% believe they will fall. Reasons given for this include the attraction of ‘growing your own’, improvements in technology and “the increased use of workflows and standardisation to allow more transactional work to be carried out at a more junior level”.

The position is reversed, however, when it comes to senior solicitors, with 19% of heads of legal expecting numbers to grow and 28% expecting them to fall. The situation is starker still at principal solicitor/team leader level, where just 9% of heads of legal expect a growth in numbers and one in four (25%) expect a reduction. In time this could present serious management challenges if there are limited opportunities for the junior lawyers to progress their careers.

Controlling external spend

A recurring theme ever since we started our research almost a decade ago has been the importance of controlling expenditure on external legal advice. Significantly, the latest survey reveals that in many cases the relevant budget is not held by the legal team but rather by the client department, which has to fund provision where the need is identified. This does beg the question of how much control is being exerted and whether full value is being extracted; one head of legal admits that their council is “yet to identify all external legal spend as some goes through the client direct”.

Fewer than one in ten of heads of legal (8%) expect their budget for external advice to increase by more than 5% in the foreseeable future, while more than half (54%) expect it to fall by more than 5%. “We are looking to put work out only when there is a capability issue, not a capacity issue,” says one respondent. “Things will take longer but that is the price of reducing costs.” Others point to the desire to develop in-house expertise as a key driver.

More than half of respondents (56%) still believe the cost of ‘routine’ external legal advice to be ‘too high’ (a finding common to previous editions of the research). For specialist and transactional work, the figure is (at 45%) not much lower. In both cases, just 2% of heads of legal consider the fees to be ‘good value’. These figures show no improvement on the 2013 survey – if anything they reveal a hardening of attitudes – despite the fact that panels of law firms and, to a lesser extent, barristers have been such a significant feature of the market for many years.

Almost three-quarters (74%) of respondent authorities are part of a panel or framework arrangement for law firms and a further 6% are planning to join one. For barristers, 54% of authorities use a panel or framework, with a further 12% planning to do so. Fifty-eight per cent of authorities say that they have saved money on solicitors' fees by using a panel or framework, 24% say they have reduced fees by 20% or more.

There could be further concerted pushes towards extracting lower rates or better value when these framework agreements are re-tendered, but what would the impact be on external providers if this were to happen? Some high-profile names in the sector are already noticeably absent (out of choice) when the results of legal services procurements are announced, although they are still considered to maintain a strong presence for top-end pieces of work. Further pressure on rates could see other law firms’ commitment to the sector called into question – particularly at those practices where the hourly rate for public sector partners is already significantly lower than the rate for those who generate their revenues from private sector clients.

When it comes to barristers, meanwhile, the success of panels/framework agreements has been mixed. In December 2015 the London Boroughs Legal Alliance unveiled a revised four-year framework agreement worth £25m, reducing the number of chambers chosen from 29 to 19 in the process. However, in August 2013 the North West Legal Consortium decided against continuing with its framework agreement for counsel and chose instead to establish a database of barristers’ rates.

In our latest survey one respondent reports that their department has access to an arrangement in relation to barristers but adds that “it doesn’t really work and has not saved money for some areas”. Another finds that their arrangements are “no better than ‘mates’ rates’ at preferred chambers”, the latter “saving the hassle of procurement”. Against that, 65% of those respondents that use barristers panels say that they have reduced costs.

The (unstoppable?) rise of the shared legal service

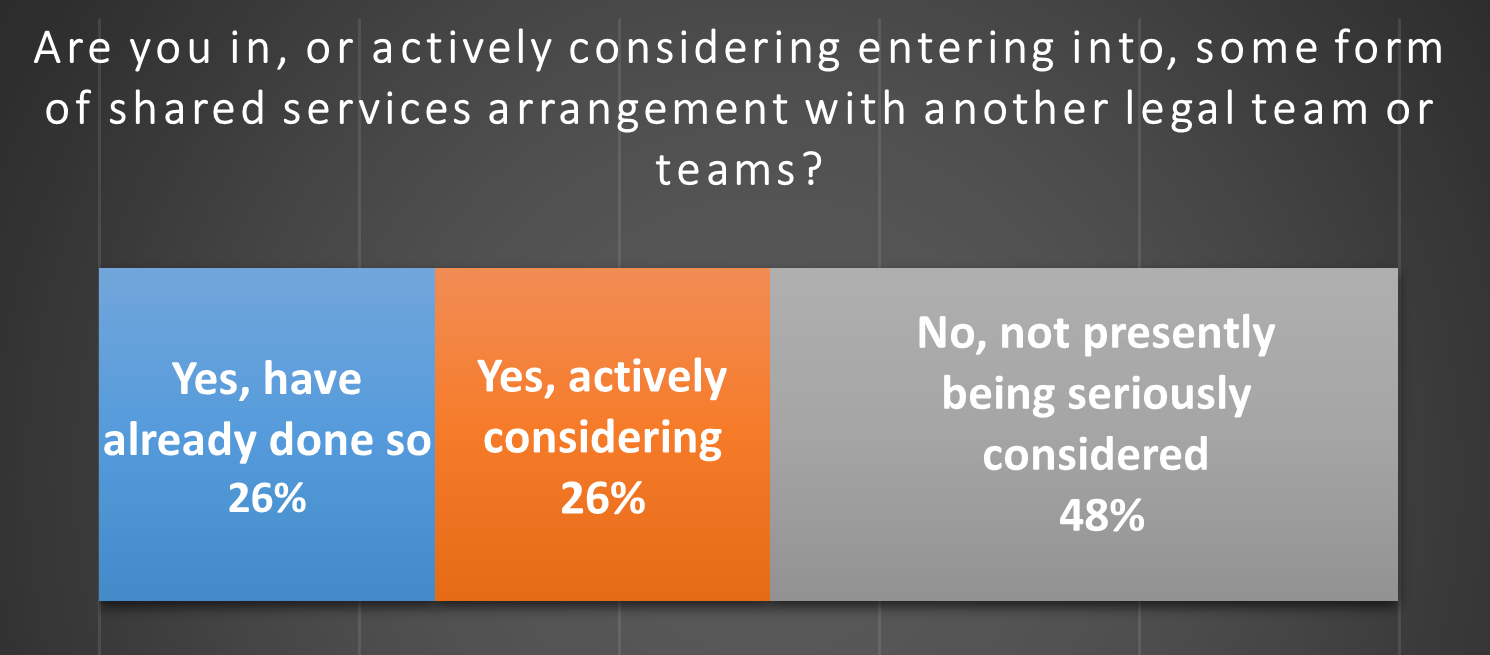

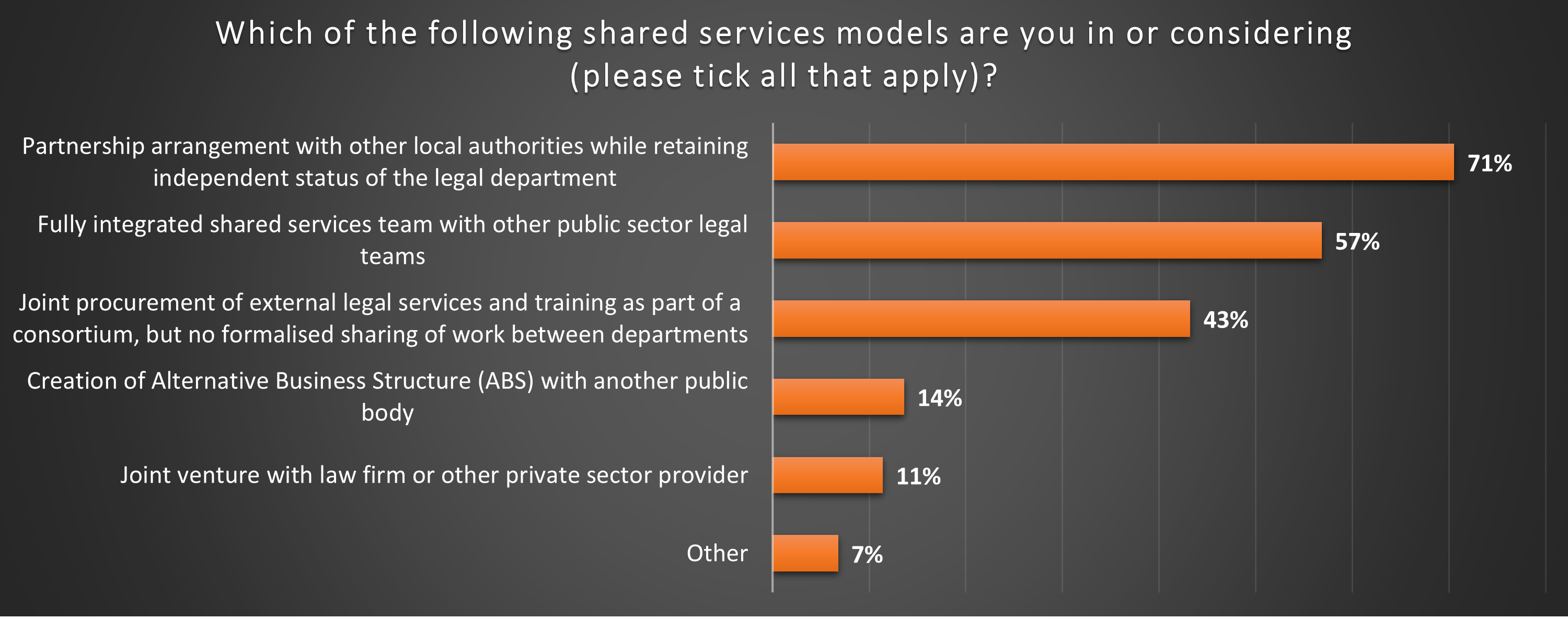

The third strategic option for local authority legal departments we asked about was setting up a shared service or joining an existing one. This year’s survey reveals that more than a quarter of legal teams (26%) are already part of such an arrangement, while the same percentage are actively considering joining or forming one.

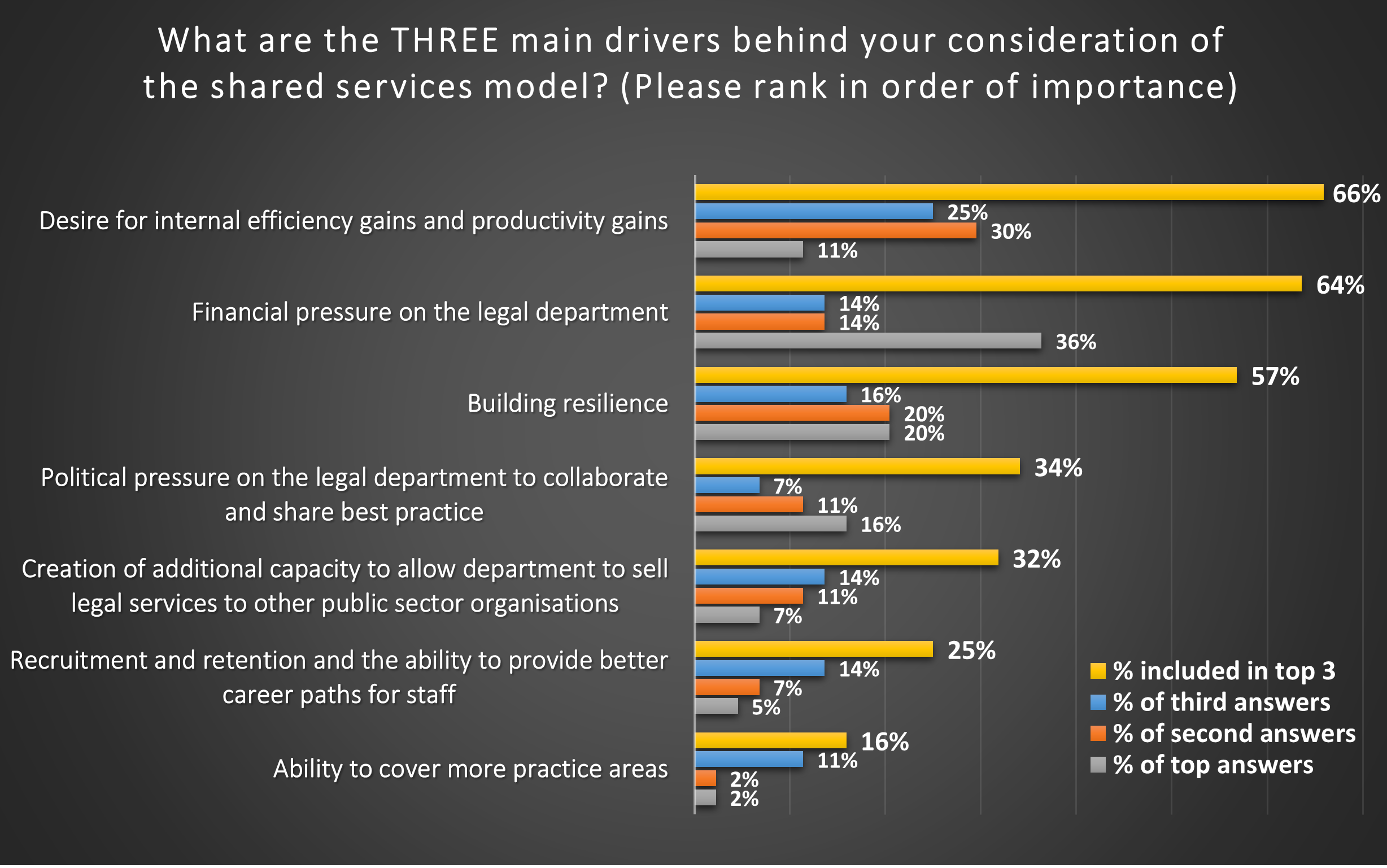

The three main reasons given by heads of legal for being part of or contemplating a shared service are the desire for internal efficiency and productivity gains, financial pressures on the legal department, and the need to build resilience.

All three were to be found – and the need to meet a £245,000 savings target for legal services was assigned particular importance – in a recent report prepared for Central Bedfordshire Council’s Executive, ahead of its decision in December 2015 to name LGSS Law as its preferred bidder for implementing a shared service. The financial advantages were also cited by Wychavon and Malvern Hills Councils for their decision to set up a shared legal service from the beginning of January this year.

One intriguing question is whether, once a shared legal service has been established, there is an intrinsic impulse for it to grow in size and scope. HB Public Law, for example, has moved well beyond its origins – as a shared service between the London boroughs of Harrow and Barnet – to encompass providing all legal services for Hounslow and Aylesbury Vale councils. Prior to its deal with Central Bedfordshire, LGSS Law started out as a service for Cambridgeshire and Northamptonshire County Councils before merging with Northampton Borough Council’s legal department in 2013. The South London Legal Partnership has also grown from being a shared legal service for Richmond and Merton to include Sutton and Kingston, and has been conducting due diligence with the London Borough of Wandsworth about a merger of their respective legal teams.

These developments contrast with the shared service for Manchester City Council and Salford Council, which has thus far stuck resolutely to its management team’s position that there would be no further growth beyond its launch in April 2012.

When it comes to shared legal services, there is of course a vast array of models that can be adopted. The proposed Orbis Public Law partnership – under consideration by Surrey, East Sussex, West Sussex, Brighton & Hove Councils and an unnamed district – appears to be a looser affiliation, with the lawyers in each team continuing to be employed by their original authority. There are a number of other collaborative arrangements, limited to initiatives such as joint training and the procurement of solicitors and legal publishing.

Despite the inherent flexibility of shared service arrangements, nearly half of heads of legal (48%) say this option is not presently being considered. The three most commonly given reasons for this are that: demand for legal advice can be met within the present structure; members and senior officers want to retain an independent legal function; and a shared service would lead to a disconnection between the legal team and internal client departments.

Making the (business) case

The survey reveals that a number of putative shared services have clearly foundered at the business case stage. “We have been through this and demonstrated that the service would not be as good and would probably be more expensive,” says one respondent. Another points to “a lack of any real evidence of shared services delivering savings which are not achievable through simpler means”. The shared service model would not deliver real, sustainable savings, adds a third, although they add that “it needs something more aggressive – real change rather than rearranging the deckchairs”.

Other heads of legal report that the idea was actively pursued around 2010/11 but there had been no appetite at the time from neighbouring authorities. Whether that would still be the case now – if the process were gone through again – is an interesting question.

For some, the potential for a shared legal service has suffered because it evokes issues over the county/district divide, whether current or historic. Another challenge highlighted by some respondents arises where potential partner authorities have different political persuasions – though this issue did not prevent the establishment of HB Public Law out of the legal teams at Harrow (traditionally a Labour council) and Barnet (Conservative).

For some, the potential for a shared legal service has suffered because it evokes issues over the county/district divide, whether current or historic. Another challenge highlighted by some respondents arises where potential partner authorities have different political persuasions – though this issue did not prevent the establishment of HB Public Law out of the legal teams at Harrow (traditionally a Labour council) and Barnet (Conservative).

In Wales, the continued uncertainty about local government re-organisation – the Welsh Government initially proposed reducing the number of councils from 22 to eight or nine – has led to the adoption of a ‘wait and see’ approach, reports one respondent.

The survey meanwhile found that a significant minority of rank and file lawyers also remain to be convinced that shared services are right for them. Some 28% say they would be less likely to apply for a job in one, with fewer than one in ten (7%) suggesting that they would be more likely to apply.

The main perceived disadvantage of working in a shared service is seen to be location (the prospect of having to move to a less attractive working environment). This was followed by: a more distant relationship with clients and the home authority; pay; and manageability of the workload. The pluses by contrast were seen to be the potential offer of good quality, varied work, and the training and career development opportunities.

Pursuing alternatives

The fourth and fifth strategic options covered by the survey – setting up an alternative business structure (ABS) and selling legal services to other public bodies – are worth considering together, for reasons that will become clear.

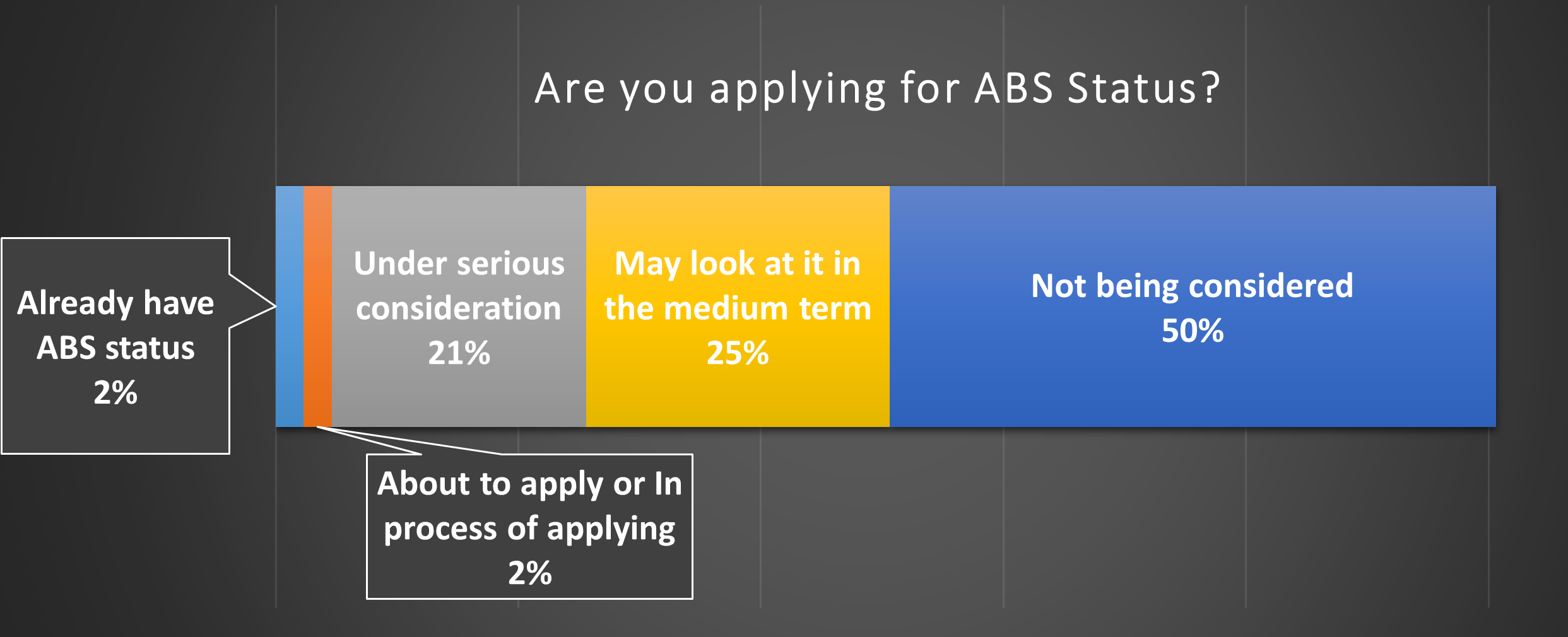

Interest in ABSs at the time of the 2013 survey was considerable, but so far only HB Public Law, Buckinghamshire Law Plus and LGSS Law have obtained licences from the Solicitors Regulation Authority, although Essex’s Cabinet recently approved Essex Legal Services’ plans to apply for one.

In this survey just 4% of respondents say their departments have set up an ABS or are about to apply or in the process of applying to the SRA. A further 21% say it is “under serious consideration”, while 25% “may look at it in the medium term”. The comment of one head of legal that he “would prefer to see how successful others are first” is a common response.

More than half of those surveyed (54%) reject the idea. “Is it simply the latest fad?” asks one respondent, while another describes it as “flavour of the month” and says they “do not consider it presently to put us in a more favourable position from a business point of view”. Another suggests that for a small team, “it has no benefit at this time”.

Interest in ABSs may well have been stirred, however, by recent comments from a senior SRA official to the effect that – in the regulator’s view – local authorities selling legal services to other public bodies beyond their immediate area are required by the Legal Services Act 2007 to do so through an authorised entity. Local authorities are not authorised entities, so their legal teams would, according to the SRA, have to set up an ABS if they want to trade further afield.

These comments came as something of a bolt from the blue to those authorities which have hitherto relied on Rule 4.15 of the SRA Handbook and empowerment statutes such as the Local Authorities (Goods and Services) Act 1970 to trade more widely.

At the heart of the issue is whether client public bodies of local government legal departments should be considered members of ‘the public or a section of the public’, for the purposes of section 15(4) of the Legal Services Act 2007. Although this issue is ultimately one for the courts to determine, the SRA takes the view that such bodies could be considered in this way. In response, Geoff Wild, Director of Governance and Law at Kent County Council, has highlighted an opinion to the contrary obtained from leading local government law QC James Goudie of 11KBW in 2013. In January, The Lawyers in Local Government Group also sought legal advice on the validity of the SRA’s view.

Trading up

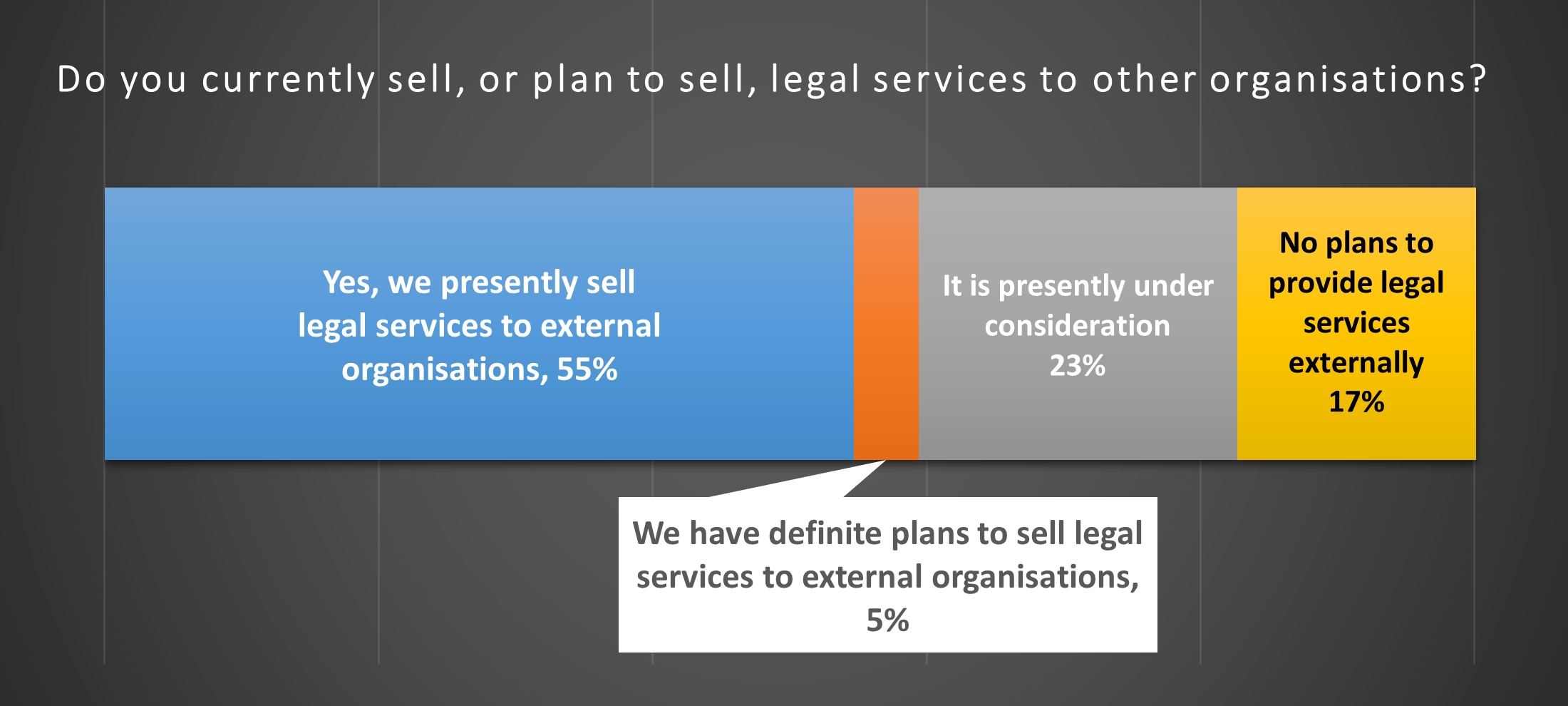

Putting the resolution of this regulatory issue to one side, legal services are undoubtedly seen as one of the prime opportunities for local authorities looking to generate additional income streams. In the Legal Department of the Future survey some 60% of heads of legal say their teams either sell or have definite plans to sell services to other organisations, while 23% say it is presently under consideration.

Fewer than one in five councils (17%) rule it out – one respondent reports “a lack of capacity due to a downsized department” and another says it is “difficult to justify when we can struggle to meet internal demand with a limited legal resource”.

There is clear recognition amongst heads of legal, however, that selling legal services to other public bodies is not without its difficulties. The top five challenges are perceived to be:

● Insufficient resources to take on the additional work (75% of heads of legal consider this is a key challenge);

● Prioritisation issues and conflicts of interest within their own authority (48%);

● A lack of sales and marketing experience (43%);

● The cost of regulation and indemnity insurance (38%); and

● A lack of internal infrastructure (32%).

Interestingly, the challenge of there being a ‘lack of demand’ is only in sixth position, suggesting fairly widespread confidence that there is a market out there. But as one respondent notes: “If everyone is trying to set up sell services, who is going to buy?”

Hitting the target

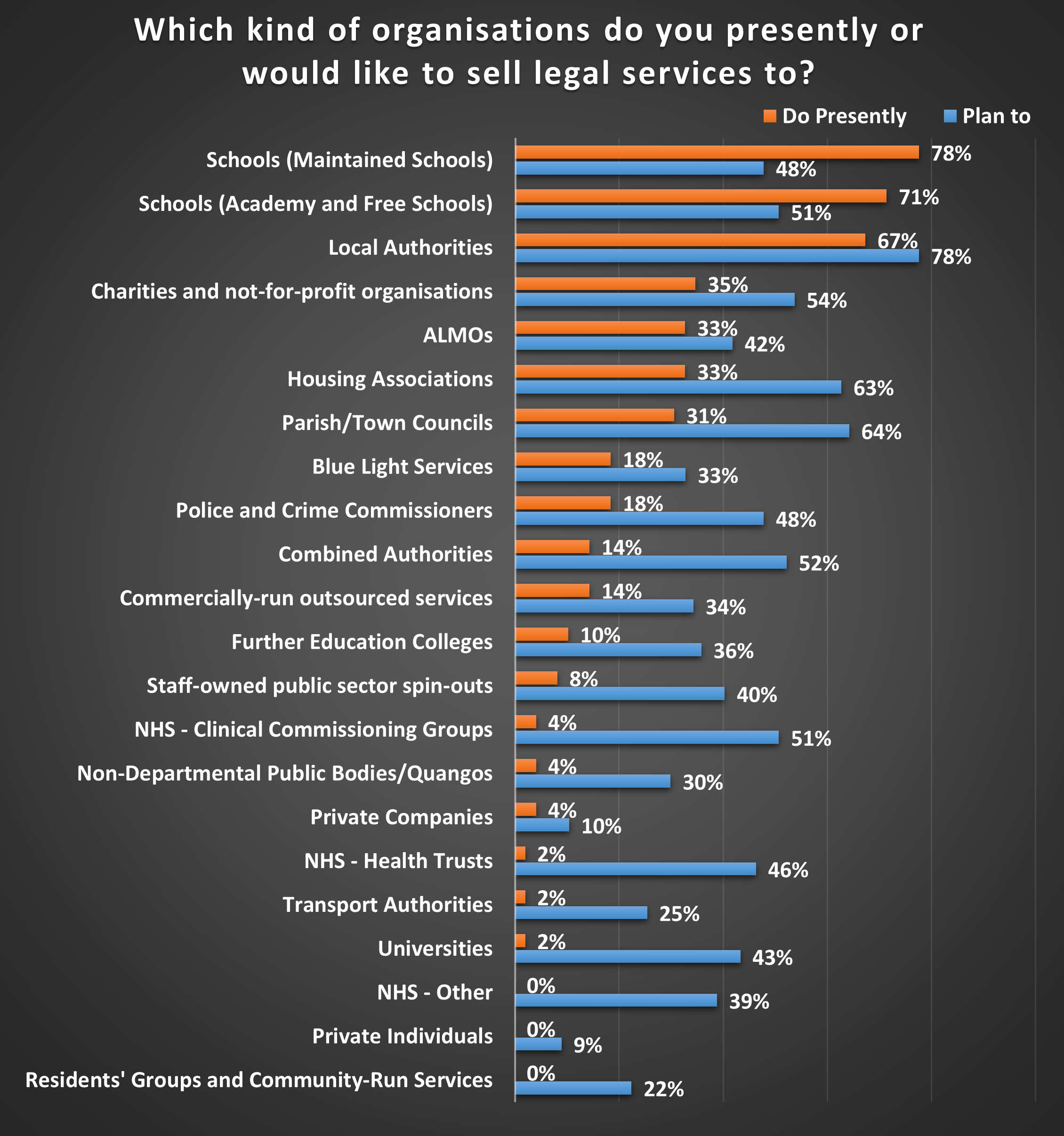

So who are these potential clients? Well, those currently selling legal services are principally selling to maintained schools (78%), academies and free schools (71%) and other local authorities (67%). These were followed by: charities and not-for-profit organisations (35%); housing associations and ALMOs (33%); parish and town councils (31%); police and crime commissioners (18%); and blue light services (18%). Recently-established organisations such as combined authorities are also a source of work for some teams (14%).

Many legal departments would very much like to cast the net more widely, however. Some 43% of respondents intend to sell legal services to universities, but only 2% currently do so. Similarly, 51% plan to sell to clinical commissioning groups, 46% to health trusts and 39% to other NHS bodies but again very few currently do so. Other ‘target’ clients include housing associations (63% of trading local authorities intend to sell to them but only 33% do so now) and staff-owned public sector spinouts (40% intend to sell to these bodies – following the client – but just 8% currently do so).

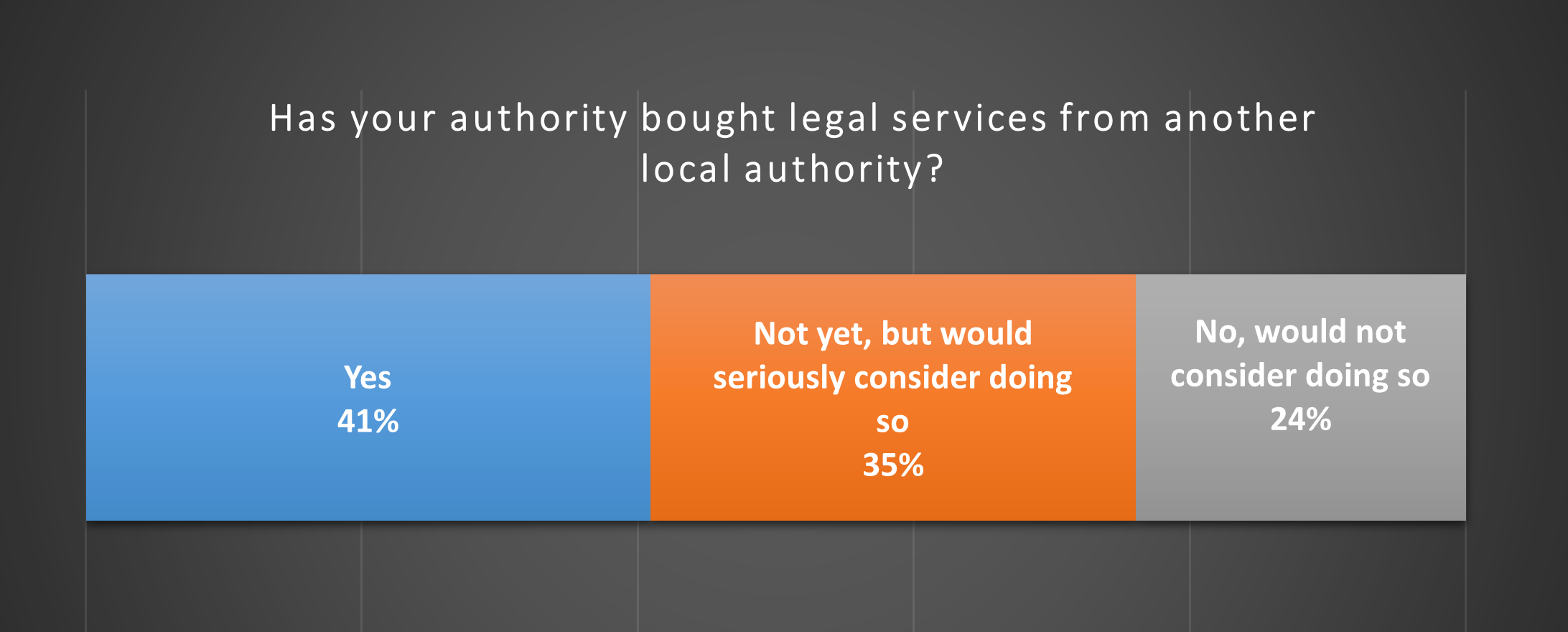

It would be naïve, though, to ignore the challenges in securing new clients and then keeping hold of them. Arguably the easiest sell is to other local authorities and in this regard the survey provides some good news. Two in five local authorities (41%) have bought legal services from another authority; a further 36% have not, “but would seriously consider doing so”. The attraction, says one respondent, is to “keep public money in the public sector”.

In many cases, the instructions from other local authorities appear to be ad hoc (rather than a steady steam), arising where the buying council has capacity or resilience issues (sickness or holiday cover), faces a conflict of interest (for example in a serious case review) or requires specific expertise more likely to be available from another legal department than from private practice.

According to heads of legal, the main perceived attraction of using another local authority is the lower cost, although some suggest that it is still cheaper to use a locum lawyer. This is followed by a better understanding of the culture of local authorities, more relevant experience than private practice, and familiarity with working practices and procedures.

What clients want

But what services do local authority clients actually want to buy? The areas where respondents say they would be most likely to use local authority providers are: employment matters (50%); litigation and enforcement (42%); procurement and contracts (38%); property and asset management (38%); planning (27%); adult social services (27%); and child protection (27%).

This differs from the five areas where heads of legal say their departments would be most likely to use private practice in future, namely: regeneration and economic development (57%); PFI/PPP and projects (51%); procurement and contracts (49%); judicial review (39%); employment (37%); and property and asset management (37%).

Local authorities do, as buyers, have potential concerns about instructing another council legal team. Chief amongst these is the potential slow turnaround of matters due to the provider prioritising its own authority’s work (81% of heads of legal included this in their top three concerns).

Other causes for worry are: the potential for there to be a permanent loss of future work to a ‘rival’ authority (43%); a lack of experience of advising a range of authorities with different procedures and cultures (35%); a lack of the necessary expertise (34%); and a lack of infrastructure/client care facilities at local authority providers (33%).

These results should provide plenty of food thought for those legal departments seeking to increase their income generation. The comments of some heads of legal emphasise just how important it is to ‘get it right’ first time. “I would be reluctant to purchase again because of client care issues and the quality of advice,” says one, while another reports that “we did have a bad experience which put us off one provider” and a third suggests that “the quality was very poor” and they “would not look to repeat”. By contrast, another respondent says they obtained external employment advice where there was a conflict of interest and reports that it “was cheaper than our service and excellent”. In designing their offerings, local authority legal teams will have to examine how they can deliver this kind of positive experience.

On a positive note, rank-and-file lawyers seem pretty open-minded about the prospect of being asked to trade legal services. Nearly two thirds of the 300+ lawyers who responded to our careers survey agreed with the statement that it was “an opportunity for me to acquire new experience and skills”. Fewer than one in four agreed with the statement that it was “a risk to the public service ethos”.

It is worth highlighting how a number of local authority legal departments have already enjoyed success in securing places on legal services framework agreements or winning individual contracts. Last year saw Norfolk-based shared service nplaw win a £100,000 contract to advise Maldon District Council in Essex on section 106 agreements, seeing off 18 rival bidders in the process.

Staffordshire County Council and Conwy County Borough Council also secured positions on various lots on panels set up by the National Procurement Service for Wales. And in December 2015 three legal teams – Kent Legal Services, Staffordshire and nplaw – won places on the revised £30-£90m legal services panels set up by HealthTrust Europe, a purchasing body for the health sector that provides support to more than 400 public and private sector organisations.

Of course, these successes come with the proviso that – as any private sector firm will tell you – being appointed to a panel is no guarantee of a steady flow of work. But they are at the very least a start.

Private sector partners

The final strategic option for legal departments that respondents were asked about was entry into a partnership or joint venture with a private sector provider. Just 11% say they are considering such an arrangement, the same percentage as in the 2013 survey.

So far there have only been a handful of such deals. The tie-up between Bevan Brittan and HB Public Law is a high-profile example, but elsewhere developments appear to have stalled.

Sandwell Metropolitan Borough Council appointed Ashfords as its sole legal provider on a three-year deal in October 2012 but this arrangement was not renewed when the term came to an end last autumn, despite internal council papers suggesting it had been a success.

Kent County Council had meanwhile hoped to have a partner in place for a ten-year, £100m joint venture with Kent Legal Services for a contract start date of 1 April last year. The procurement exercise was hit by delays, with a decision on the single remaining bidder’s proposal subsequently scheduled for September 2015. However, this decision was not taken. A spokesperson for the county council suggested that a Cabinet decision on the procurement would be taken later in the autumn of 2015, but this timeframe again passed without any further developments (at least publicly).

Interestingly, the option of a direct partnership with a private sector firm was considered by Central Bedfordshire and discussions were held with three leading practices, but this approach was rejected “on the basis that it is highly unlikely to make any savings and in all probability would prove more expensive”.

Seizing the day

Taking the results of the Legal Department of the Future survey as a whole, it would seem that there is no consensus yet on how local authority legal departments should respond to the financial pressures they are under. The survey reveals there is still a wide range of (often strongly-held) opinions on the merits of strategies such as shared services, alternative business structures, trading and framework agreements. However, it does appear that some departments have significantly more control over their destiny than others. Which side is your team on?

Philip Hoult is Editor of Local Government Lawyer and Public Law Today.

This article appeared in the Legal Department of the Future report, published in February 2016. To read or download the full report, please click on the following link: http://www.localgovernmentlawyer.co.uk/ldotf/

This article appeared in the Legal Department of the Future report, published in February 2016. To read or download the full report, please click on the following link: http://www.localgovernmentlawyer.co.uk/ldotf/

Litgation Solicitor

Solicitor - Civil and Criminal Litigation

Commercial Lawyer

Legal Director - Government and Public Sector

Solicitor - Civil and Criminal Litigation

Solicitor - Contracts and Procurement

Head of Legal

Child Care Lawyer

Locum roles

Cornerstone Barristers roundtable on the Draft NPPF: Plan-Making Provisions

Cornerstone Barristers roundtable on the Draft NPPF: Plan-Making Provisions

09-02-2026 2:00 pm

London

Breakfast Briefing – Commonhold & Leasehold Reform Bill – a session focusing on the key themes of the Bill and the Consultation on Banning Leasehold for New Flats - Devonshires

Breakfast Briefing – Commonhold & Leasehold Reform Bill – a session focusing on the key themes of the Bill and the Consultation on Banning Leasehold for New Flats - Devonshires

12-02-2026 8:30 am

London

Planning, Property and Power Webinar Series: Strategic energy planning - Landmark Chambers

Planning, Property and Power Webinar Series: Strategic energy planning - Landmark Chambers

12-02-2026 10:00 am

Online (live)

Public Sector Insights – NHS Continuing Healthcare (CHC) in Wales - Blake Morgan

Public Sector Insights – NHS Continuing Healthcare (CHC) in Wales - Blake Morgan

12-02-2026 10:00 am

Online (live)

InLaws workshop – Effective Communicating and Influencing - Devonshires

InLaws workshop – Effective Communicating and Influencing - Devonshires

12-02-2026 2:00 pm

Online (live)

HMPL Building Blocks: Legal Tools to Combat Anti-Social Behaviour - Devonshires

HMPL Building Blocks: Legal Tools to Combat Anti-Social Behaviour - Devonshires

17-02-2026

Online (live)

Data Controller, Processor or Joint Controller: What am I? - Act Now

Data Controller, Processor or Joint Controller: What am I? - Act Now

18-02-2026 10:00 am

Online (live)

Freedom of thought, belief and religion: Article 9 ECHR - Francis Taylor Building

Freedom of thought, belief and religion: Article 9 ECHR - Francis Taylor Building

19-02-2026

Online (live)

AI and Information Governance: Bridging Innovation and Compliance - Act Now

AI and Information Governance: Bridging Innovation and Compliance - Act Now

19-02-2026 10:00 am

Online (live)

Safeguarding Issues and Fairness in Investigations and Hearings - 3PB

Safeguarding Issues and Fairness in Investigations and Hearings - 3PB

24-02-2026 11:00 am

Online (live)

Children and Young People (DoL, Competency and Capacity) - Peter Edwards Law Training

Children and Young People (DoL, Competency and Capacity) - Peter Edwards Law Training

25-02-2026

Online (live)

The General Data Protection Regulation - Act Now

The General Data Protection Regulation - Act Now  Interveners in financial remedy proceedings - 42BR

Interveners in financial remedy proceedings - 42BR  The Procurement Act - One Year On - DWF

The Procurement Act - One Year On - DWF  The ERA – An Overview - Sharpe Pritchard

The ERA – An Overview - Sharpe Pritchard  Short Term Lets - Ivy Legal

Short Term Lets - Ivy Legal