The race for talent

The recruitment market for qualified local government lawyers is the tightest that it has been for years. At a time when council legal teams are busier than ever it is putting a severe strain on legal department management writes Derek Bedlow.

When Local Government Lawyer first conducted a version of the careers survey in 2012, problems with recruitment and retention barely registered in the list of challenges facing local government legal departments as they dealt with the effects of the cuts to local authority budgets in the Comprehensive Spending Review (CSR) of 2010.

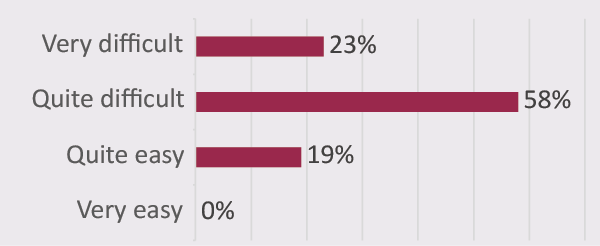

What a difference seven years makes. Now, in 2019, recruitment and retention has become the biggest single issue facing local authority legal departments as the volume and complexity of legal work increases. The vast majority (87%) of the 76 heads of legal who took part in the survey agreed that the recruitment of qualified staff is “difficult” with 39% describing it as “very difficult”. “There is a lack of good lawyers willing to enter the public sector,” lamented one head of legal (FIG 1).

| Figure 1: In general, how easy or difficult is it to hire good lawyers in the present market? |

|

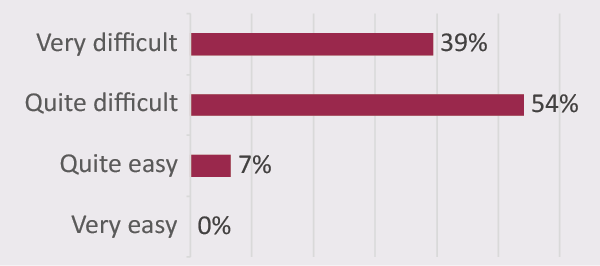

The situation is unlikely to improve in the immediate future. Close to half of heads of legal (44%) (FIG 2) expect the recruitment of qualified staff to get harder still in the foreseeable future while none of the respondents to the survey expect it to get easier. As outlined in the first article of this report, escalating volumes of work mean that demand for lawyers is to grow further.

| Figure 2: How is this likely to change in the foreseeable future? |

|

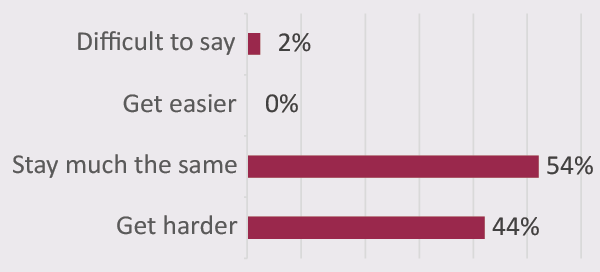

Moreover, and in contrast to earlier surveys of legal department management, many legal departments now want to have more experienced senior lawyers in their ranks. In the last Legal Department of the Future survey in 2015, the majority of respondents predicted that the number of principal and senior level solicitors would fall, while the proportion of less experienced and, particularly, paralegals would expand. In this year’s survey, heads of legal forecast that they will need more (FIG 3) senior lawyers as well as more junior ones. “New work is tending to be complex, requiring senior practitioners,” said one respondent.

Figure 3: Of your lawyers at the following career levels, which do you expect to increase or decrease in numbers in the foreseeable future?

Recruitment problems apply to most practice areas but are especially acute in the fields of child protection, adult social care, procurement, planning, regeneration and property as well as litigation and governance, according to survey participants. Lawyers are one of the few occupational groups in local government to have survived with their numbers relatively intact since the Comprehensive Spending Review cut local authority funding in 2010. According to the Law Society’s Annual Statistics Report 2018, published in August, the number of solicitors in local government was 4409 compared with 4631 in 2010, a fall of 4.7%. In the same period, the number of employees in local government (including police and education) as a whole fell by 27%, according to the Office for National Statistics.

|

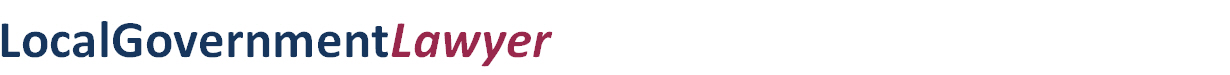

What do local authority lawyers look for in an employer? The careers survey asked 420 practising local authority lawyers what they looked for in a potential employer and by some distance, work-life balance and flexibility are the biggest factors in lawyers’ choice of employer than either pay or quality of work. This represents a marked change from the last time this survey was taken in 2015 when pay/pension was the biggest single factor, a recognition of the lack of control that many local authorities have to raise pay and the lack of significant differential between the pay and pension packages offered by different local authorities. Fortunately, two of the three most important categories – work-life balance and quality of work – are those that local authorities score quite highly on when it comes to employee satisfaction levels. But, as with pay, the question for recruiting local authorities is how to demonstrate they can deliver on these factors better than their rivals (FIG 4). |

The reasons for the spike in demand for local government lawyers are well documented, but the reasons for the lack of supply more numerous.

Pay is perhaps the most obvious problem for local authorities when it comes to attracting and keeping lawyers. Since the CSR in 2010, local authority staff have had an effective pay freeze which has left average local authority lawyers’ pay well behind their peers in private practice and other parts of the public sector. Lawyers in areas such as procurement or planning can earn £80-£100K in a commercial law firm, compared with £35-50K in local government.

Even after the lifting of the public sector pay cap, salary rises for local government lawyers have remained subdued. Average salary figures for 2018, as measured by an analysis of the listings on Local Government Lawyer’s jobs board Public Law Jobs, show that when compared with 2017, average base salaries for in-house local government lawyers increased by 3%, leaving them at an average for qualified lawyers of between £39,290 - £44,320.

This is despite a rise in the number of vacancies (the number of jobs advertised on Public Law Jobs increased by more than 50% – from 430 to 636 – from 2017 to 2018) and a tightening job market in both public sector legal and in the profession generally.

Pension provision for local authorities has also become less generous than it was although local authority defined benefit pensions are still more attractive than most schemes found in the private sector, where defined benefit schemes are almost impossible to find. Estimations of the compatible value of public sector pensions vary, but research by the National Institute for Economic and Social Research in 2016 (Workplace Pensions and Remuneration in the Public and Private Sectors in the UK by Jonathan Cribb and Carl Emmerson) found that the immediate monetary value of a public sector pension equated to 14% of salary, compared with less than 3% in the private sector.

This suggests that, for comparison purposes, an additional 11% should be added to public sector salaries to reflect the enhanced pension provision offered by local authorities although the additional value of the certainty provided by ‘defined benefit’ public sector pensions over the ‘defined contribution’ schemes almost universally offered by the private sector is more difficult to calculate.

| Figure 4: What are the THREE most important factors in deciding where you work? (Please rank in order) |

|

Please click above table to enlarge. |

The use of ‘market supplements’ and similarly-worded additional payments has risen significantly, from 4% of all roles advertised on the Public Law Jobs website in 2017 to 12% in 2018. They are most prevalent amongst councils in the South East (excluding London), 25% of whose vacancies included an additional payment of some description. However, these do not appear to be a panacea for councils with recruitment problems – these are often not guaranteed indefinitely for successful candidates and, as was pointed out by a number of respondents to the careers section of the survey, can lead to resentment amongst existing staff.

|

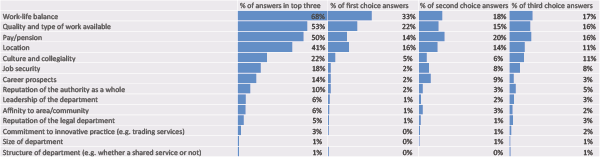

The skills gap Which skills will be essential for lawyers in local government in the future? We asked both heads of legal and other local government lawyers what they saw as being the most important attributes to work in local government law (FIG 5). Figure 5: Which skills will be essential for lawyers in local government in the future?

While there were many areas of agreement, there were also some interesting differences of opinion. In the top three, for example, technical legal knowledge and problem-solving skills are both valued highly by management and staff alike, but ‘adaptability’ is an attribute valued much more by heads of legal than by rank-and-file lawyers as are negotiation skills, technological skills and people management skills. In the opposite direction, staff are more likely than their management to think that legal analytical skills, communication skills and, above all, knowledge of local government structures and culture will be important skills in the future. The survey also asked lawyers whether they preferred to be generalists or specialists. 60% of lawyers asked said they would prefer to specialise, a small rise on the 58% who said the same thing when this survey was last conducted in 2015. “We always have specialists advising the other side. We need to [be able to] represent our clients properly,” said one respondent. “I want to be good at what I do,” said another. For those who preferred to remain generalists, the variety of work on offer was the main attraction. “A huge benefit of being a local government lawyer is good variety of work,” said one while adding that the pace of change in the law made over-specialisation more difficult. “The days of specialism are gone – the law has changed so much and is constantly changing further [and] with the advent of Google everyone has access to the law. It is a matter of being able to adapt and thrive in these invigorating times.” In the open comments to this question, quite a number of respondents also brought up the issue that local government career structures reward those who move into management but not those who become highly technically proficient in their area of law. “I would prefer to be a specialist if I was to remain in my role but to progress it is essential that you have a sound knowledge of all aspects of the work,” said one.

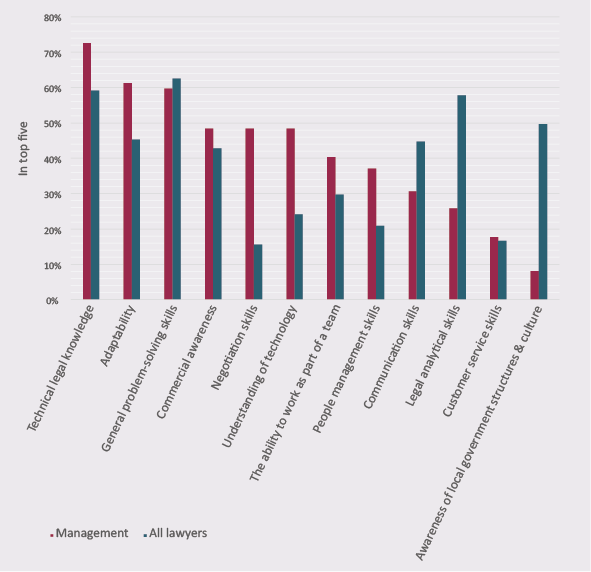

Finally, local government lawyers were asked about the training they received. Worryingly, 30% of those surveyed said they did not feel that they received enough training to do their jobs, a rise of 2% on answers to the same question in 2015 and 7% when the same question was asked in a similar survey by Local Government Lawyer in 2013 (FIG 6). Many put this down to the withdrawal of funding for expensive bespoke courses, especially since the ending of 16-hour minimum hours of the CPD regime and the consequent reliance on free training resources. “Since the CPD requirements of the Law Society were relaxed, I feel my manager has used it as an excuse to limit external training, and we do very little internal training,” said one in-house lawyer. While many say that the quality of much of this training is good as far it goes, finding free or low-cost training that is relevant to specialist areas of practice is much more difficult. “The lack of an available training budget means that we are totally reliant on free training provision from panel firms on EU procured frameworks,” said another in a similar vein. “Whilst those training courses are good, they are, by their nature, not particularly detailed and they are really a scatter gun of issues covered in a very short space of time meaning that there is little benefit to attending some of them.” A number of respondents also noted that the lack of training budget is hampering legal departments’ efforts to save cost by retaining more work in-house. “I have adequate training to do the run-of-the-mill aspects [of my job] but would like the opportunity to refresh skills and learn new ones which are needed as restricted funding will mean we will not always be able to instruct the expertise needed,” said one. Nevertheless, there seems little expectation that training budgets are likely to improve in the immediate future. When asked how they expected training to be delivered in the future, most expected the use of free (especially online) training to grow (57%), while almost half (48%) expected further cuts to their paid-for training budgets. |

Even with market supplements and the pension advantages, public sector pay freezes have left local authority lawyer salary packages some distance behind those offered to those with similar post-qualification experience in private practice. Moreover, the lack of significant differential between pay and other benefits offered by individual local authorities means that there is little incentive to move jobs for financial reasons.

The structure of most legal departments means that promotion – and higher pay – is often only open to those prepared to take on management responsibility – there is little financial reward for developing technical expertise. Consequently, in the more in-demand disciplines, experienced lawyers can also earn significantly more by working as a locum than permanent staff, despite the effect of the IR35 changes to the tax status of locum lawyers which deemed many to be ‘employees’ for taxation purposes rather than contactors. According to respondents to the heads of legal survey, the imposition of IR35 has not dented the use of locum lawyers by local authorities, only made it more expensive (FIG 7).

| Figure 7: What difference has the imposition of IR35 on locum solicitors made to your use of locums? |

|

|

|

Ask not what your staff can do for you… One of the questions in this year’s survey asked what steps could your employer take to improve the working environment for you? Offhand comments ranged from the light-hearted (“Move the busker on from outside our office”) to the angry (“Listen !!”) but in reading the more considered responses a clear set of requests begin to emerge. Nobody is demanding trendy offices with bars, ping pong tables and bean bags dotted about the work floor. Local government lawyers responding to our survey have their eyes set on more conservative changes to the office environment. In particular, many suggested that the adoption of open-plan offices has led to “crowded” and “noisy” spaces which hinder the focus needed for legal work. Break out spaces that would offer quiet areas for working are suggested here but still, the chorus of lawyers wishing to get rid of “horrid” open-plan offices overpowers the compromising voices. Hot desking appears to be causing issues in the office environment too. One respondent noted that “tensions rise over territorial claims” with staff claiming certain desks for themselves. Many would prefer their own desk but where hot-desking is not likely to go away, some respondents suggested that a solution could lie in increasing the number of desks available. If increasing desk space is not possible, one commenter said that an “increase [in] working from home flexibility” was essential. For most councils short on desk space, the viability of hot desking is dependent on a successful flexible working scheme. But flexible working is not only seen as a solution to the lack of workspace in council offices; where flexible working is being implemented, our respondents hailed their ability to work from home and choose their hours as an important counter to the pay sacrifices necessary for working in local government: “My employer offers good flexible working to make up for the fact pay increases are unlikely and we do not get bonuses. They need to maintain this flexible working arrangement.” The ability to work from home and choose your hours is slowly becoming commonplace in local government, but still, three-quarters of those referencing flexible work are still waiting for it to be implemented at their councils with a lack of IT often cited as the primary barrier. Finally, the number of comments calling for better administrative support have shot up since the last time this survey was conducted in 2015 and gripes over the lack of support staff and facilities were amongst the most prevalent in this year’s survey. In return, many suggest, the productivity benefits would outweigh the cost. |

The lack of supply has been exacerbated by local authorities cutting back on training contracts in recent years. The current pool of in-house solicitors in local government is around 4500, yet there were only an average of 83 new training contracts per year over the three years to 2017, according to the Law Society.

As the age profile of solicitors in local government is quite high compared to the legal profession as a whole, this in-flow of trainees is inadequate to compensate for those leaving or retiring.

This gap has always existed to some extent but in the past, it was made up by hiring junior lawyers from private practice – a source which is less fertile than it once was and not just for financial reasons, as one head of legal told the survey: “The key perception that I've had to overcome [with lawyers from private practice] is that to move into local government is to prevent a move elsewhere in the future.”

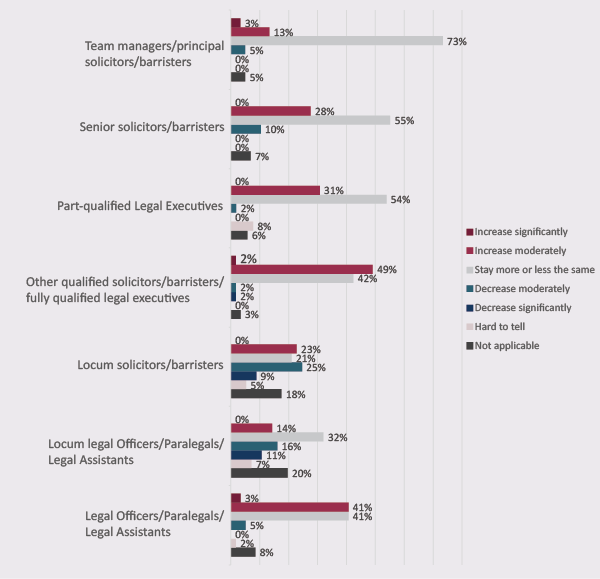

Additionally, as another respondent pointed out, while local government still offers better flexible working opportunities than private practice firms, many of the latter have made significant strides in improving the work-life balance of their staff, reducing the clear advantage that local government once enjoyed. Consequently, 81% of heads of legal said that they found it difficult to recruit from private practice (FIG 8). “You need to find someone who wants a different lifestyle and/or better pension in exchange for reduced salary and status,” commented one.

| Figure 8: In general, how easy or difficult is it to hire lawyers from private practice in the present market? |

|

|

Fighting back in the war for talent

There is widespread acceptance that the number of training contracts in the local authority legal departments – which rose to 96 in 2017/18 – needs to increase significantly and, to this end, the Lawyers in Local Government Group (LLG) is formulating a new national campaign aimed at encouraging graduates to apply for training contracts.

There is also some recognition that a career path needs to be available once that contract is completed. In contrast to most law firms, it remains common for local authority trainees to have to find a role elsewhere at the end of their training period. This puts local authorities at a distinct disadvantage with private practice where the trainee retention rate is a key metric when trying to attract law students.

Legal apprenticeships, in which A-level students or graduates join an employer without going to law school and work towards their qualification through the legal executive route are also growing in number but neither address the more immediate problem of finding experienced staff.

In the meantime, unless the funds can be found to bring qualified salaries closer to their private practice counterparts, the recruitment crisis faced by local authorities shows little sign of abating.

Derek Bedlow is the publisher of Local Government Lawyer. He can be reached at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it..

This article appeared in the Legal Department of the Future report, published in November 2019. To read or download the full report, please click on the following link: http://www.localgovernmentlawyer.co.uk/legal-dept-of-the-future