- Details

The role of offsetting in local government climate change plans

![]() An important area for local authorities to consider as part of their decarbonisation plans is offsetting. Regrettably, this is in danger of becoming mired in controversy, with a widespread misunderstanding of its legitimacy and the role that it could properly play in those decarbonisation plans, write Steve Cirell and Steve Gummer.

An important area for local authorities to consider as part of their decarbonisation plans is offsetting. Regrettably, this is in danger of becoming mired in controversy, with a widespread misunderstanding of its legitimacy and the role that it could properly play in those decarbonisation plans, write Steve Cirell and Steve Gummer.

Background

The targets that have been wound into UK law under the Climate Change Act 2008 (as amended) are very challenging. Recent reporting suggested that the world has already surpassed 1.1 degrees Celcius of global warming since pre-industrial times and reaching the international target of remaining below 1.5 degrees now seems remote.

At a local level, a majority of local authorities have declared a climate emergency and set targets for reaching the position of net zero carbon. Even those that have no emergency declaration have normally adopted similar targets. Many of those targets are to secure net zero by 2030 – just seven years away.

Action plans are addressing energy generation, energy efficiency of buildings and transport as key areas and setting down actions to move emissions inexorably downwards. However, the focus here is not on the emissions that are reduced by such actions, but on those that cannot be removed. Of course, no local authority providing services can be entirely zero carbon. The Government’s targets under the 2008 Act mentioned above are to reach a position of net zero carbon. This means that emissions are reduced as far as is humanly possible by work of the nature mentioned above, but then the impact of the residue of emissions (those that cannot be removed) is compensated for by activities that reduce carbon emissions by the same amount. This is the principle of offsetting.

When considering offsetting it is important to stress the proper hierarchy, which is 'calculate, avoid, reduce, offset'. In simple terms, this means that local authorities should calculate their carbon footprints first (to ascertain their starting point and to gauge the actions required to reach net zero), then seek to reduce energy use, avoid carbon emissions where possible (such as moving the fleet to EVs and insulating buildings) with offsetting being the last resort. It is vital that any organisation does not see offsetting as a lazy means of avoiding the real work required to deliver the targets. Whilst the private sector has been accused of this on occasion, local authorities cannot be complacent about this either.

But whatever action is taken, there will be a rump of emissions at the end that cannot be removed. This raises a timing issue – does the hierarchy mentioned above demonstrated through good practice mean that an organisation has to wait until the end to actually address offsetting? Common sense suggests no.

A linked point is that carbon offset funds will undoubtedly increase in price as 2030 approaches. If that route were taken (there are others, as discussed below) then waiting would not offer value for money for local taxpayers. However, the smart money is not on that route, but on local authority-driven, local action that provides the same benefits in a much simpler and more cost-effective way.

The definition of offsetting

The International Carbon Reduction and Offset Alliance define offsetting as follows:

“In simple terms, carbon offsetting is a mechanism used to compensate for corporate or individual carbon footprints through the purchase of carbon credits issued by accreditation standards to projects that remove greenhouse gas emissions from the atmosphere or avoid generating the emissions in the first place. Each credit is equal to one tonne of CO2(e) that has not been emitted. Once purchased, the credit is then retired through an internationally recognised and publicly viewable registry.”

This definition needs a bit more explanation before the concept can be fully clear.

Firstly, let's be clear that the sort of actions described here is 'voluntary offsetting'. The other side of the coin is provided by regulated markets for offsetting which are only relevant to individual countries and Governments and are provided by international treaties and cover areas such as heavy industry. Voluntary markets are where an individual, company or public body wants to take action to reduce a carbon footprint. These offsets are not set down by law, hence the term ‘voluntary’. Solutions under such markets are still being developed.

Offsets can also be either ‘removal’ or ‘avoidance’. Removal credits stem from activities that absorb or pull carbon out of the atmosphere, such as nature-based solutions, particularly reforestation. Avoidance credits, on the other hand, come from projects that reduce emissions by preventing their release into the atmosphere in the first place, an obvious example being energy efficiency works.

Offsetting work can also be either direct or indirect. Direct action is where the Council takes specific steps itself to do something that reduces emissions, such as better insulating and heating buildings. Indirect action happens when someone else is taking the action (but the Council’s carbon footprint is benefitting), such as entering into a Power Purchase Agreement to buy renewable energy from a local generator or switching to a green electricity tariff.

The final issue is governance. Voluntary offsetting mechanisms are not covered by the international treaties mentioned above and so are open to abuse. Problems that have occurred in the past include double counting (more than one party claiming the same credit), non-additionality (the project would have happened anyway), permanence (ten years later the trees have died) and leakage (projects that superficially reduce carbon but in fact create higher emissions elsewhere). If any of these are present, voluntary offsetting schemes lose creditability. These are the primary reasons that activists, such as Greta Thunberg, do not support offsetting, calling it ‘creative accounting’.

Offsetting in local government

Having explained the landscape of offsetting, the following principles emerge from this analysis:

- of the regulated and voluntary markets, only the latter is relevant to local authorities

- it is essential to have in place a Climate Change or similar strategy, to have committed to net zero carbon targets and have set down some form of climate action plan

- calculations have to be on the basis of a baseline carbon footprint having been established, although there is some flexibility in what is included in this

- action plans should include direct action to reduce emissions, such as insulating buildings and moving vehicles to EVs, but may also include indirect actions

- the hierarchy for emissions is calculate, avoid, reduce, offset – where offsetting must be the last resort

- offsetting only has a role in supporting climate action where there is a strong commitment to direct action and demonstrable delivery of change

- where offsetting is relevant, projects must be real, verified, permanent and additional in nature.

Options for offsetting in local government

Local authorities across the land are in the process of deciding what type of offsetting they will engage in. Broadly, there are three options: international action, national action or local action. Unsurprisingly, the latter is the one to go for.

International action has largely been in the context of the international treaties and the Clean Development Mechanism developed under the Kyoto Protocol and involves areas such as the provision of water pumps in India, improved cookstoves in Cambodia, biomass boilers to replace fuel oil in the sugar industry in Argentina or developing wind farms in Turkey. An offset fund invests in projects and offset credits are subsequently sold on the basis of that work.

National action is closer to home but still outside the area of any particular local authority. It might be presented as a large forestry project in Scotland or a peat restoration project on the East Coast. If properly organised, this would provide offsetting in which a Council could participate.

However, the simple question is why would a local authority offset so far afield, either internationally or nationally, when there are local projects to be undertaken, which will have a much more beneficial outcome in their own area?

Direct and indirect action locally

A good place to start on direct action is with renewable energy projects. If a local authority plans, commissions and constructs a new solar farm on its land, then it is able to offset the carbon value of that asset against its carbon footprint. This is because this new, renewable energy is alleviating the need to draw dirty, brown electricity from the grid.

The earliest example of this was in Cornwall Council, which in 2012 built the first civic solar farm in the country, next to Newquay Airport. A parallel, but different, example from that era was Wrexham CBC in North Wales fitting solar panels to 3,000 Council houses in its stock. This prevented the need for grid-based electricity in those properties and again this can be offset.

A very different type of direct action would be in relation to nature-based solutions. Here the removal factor is in play, as opposed to avoidance. Probably the most often quoted example of offsetting activity of this type is tree planting. Many authorities have tree planting schemes under consideration, whether for offsetting or wider biodiversity reasons.

The reason that trees and other plants are such an important part of the carbon cycle is that they accumulate carbon as part of the growing process. As every child learns in school, plants rely on a process called photosynthesis to use the energy from light in order to convert carbon dioxide and water into carbohydrates (which are needed as building blocks for plant growth) and oxygen (as a waste product). So trees literally suck in CO2 and breathe out oxygen. Projects that deliver new trees to benefit the removal of greenhouse gases can be counted as an offset.

A couple of points can be made here. Firstly, it is not simply a case of ‘plant more trees’: they need to be the right trees, planted in the right area in the right way. Expert help will be needed to get this right. Industrial plantations of species such as pine will not have the same impact as their biodiversity value is much lower than with the original indigenous forests.

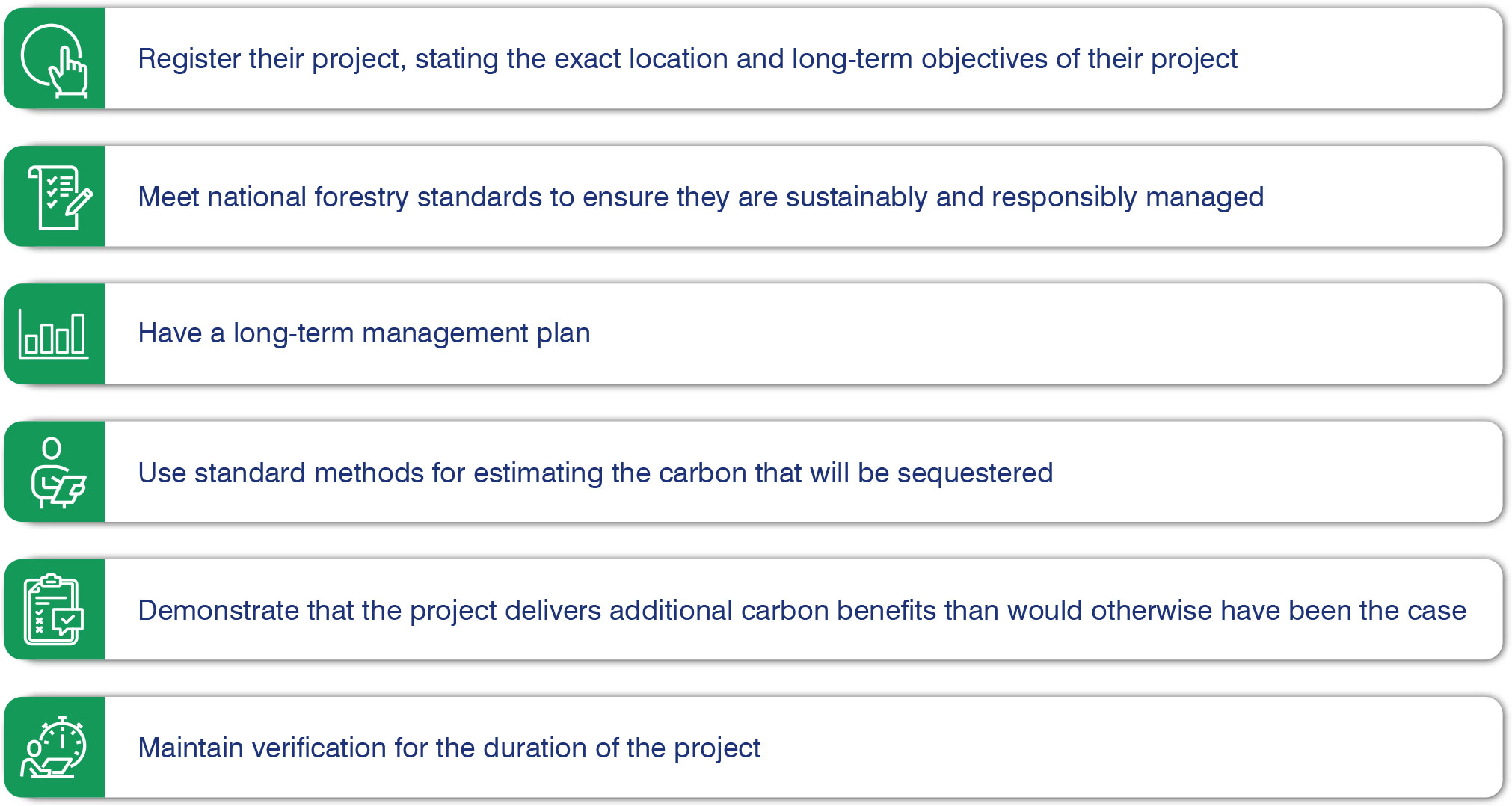

Secondly, such projects must be new, accredited and monitored, for example under the Woodland Code. Data on the number and carbon value of all new plantations needs to be carefully maintained. To meet the requirements of the Code, projects must:

These elements go to the governance of the project, as discussed above. If a local authority wishes to properly use forestation as part of its offsetting plans, it will need to address these issues. Cornwall Council offers some good examples of this type of activity too.

Turning to indirect action by a local authority, the first example to consider is the procurement of energy. All local authorities procure the oil, gas and electricity that they use in their operations on a day-to-day basis. Often this is by way of one of the purchasing organisations and traditionally covered fossil fuel supplies. Two ways that this position can be changed are by choosing a green tariff or entering into a Power Purchase Agreement.

Unfortunately, purchasing a green tariff is more complicated than might be imagined. This is because a lot of electricity that is promoted as ‘green’ is not really green at all. This is the scandal that involves REGO certificates being used to greenwash fossil fuel-based energy.

To ensure that the supply under a ‘green’ tariff is genuine, the council needs confirmation that the supplier has bought the electricity from a renewable energy generator directly; that REGOs are still attached; confirmation that the REGOs will be retired on their behalf to prevent them being re-used elsewhere; and confirmation that the revenue that will be generated will be used in new renewable energy projects. If it does this, it can count the carbon benefit against its carbon footprint.

The other way that procurement of energy can be improved is by entering into direct Power Purchase Agreements(PPA). This is a topic previously covered by the Green Steves but provides a good example of an offset opportunity.

To recap, a PPA is just a technical name for a long-term contract whereby a local authority agrees to buy electricity directly from an energy generator. Such arrangements benefit both generator and purchaser. On the generation side, it is important for the developer of any project to be sure that it can sell the output generated, so that a financial return can be achieved. The PPA gives certainty for the generator that the power will be purchased on a long term basis. For the user of the power (ie the local authority) the key is that the link between the electricity supplied and energy price inflation has been broken. This is because a price based on the cost of generation is negotiated (with an agreed index applied such as RPI or CPI), which will always in effect offer a discount on retail prices.

Whilst the power under a PPA may not be any cheaper than electricity bought currently on the markets, it has cast iron carbon credentials and as such under the right circumstances can be netted off the local authority’s carbon footprint, thereby giving it valuable progress towards its net zero carbon targets.

How offsetting works

The real nitty gritty of offsetting is how and when the carbon benefit from an activity or project is taken into account. This will not be possible on all occasions.

As an example, where a local authority fits solar panels to its council offices, it does not get any direct offset benefit from that work. This is because solar panels reduce the amount of electricity supplied by the grid to the building and therefore the carbon footprint of the authority goes down automatically (by emissions avoided). As the carbon benefit has already been taken into account in this way, it cannot be double-counted.

However, if the council develops a new solar farm and the electricity is not to be used on-site, then it would be able to take into account the carbon benefit of that generation and deduct it from its carbon footprint. There are many examples of councils proposing to build a solar farm and then counting the carbon benefit in this way.

Turning to buildings, if the council puts solar PV on commercial buildings that it owns but are occupied by a third party, then again, the council can count this against its carbon footprint, as long as it does not choose the energy supplier and pay the energy bills for the building. As an example, Warrington Borough Council has fitted solar PV to buildings it does not own or occupy and seeks to claim the carbon credit for so doing.

Similarly, for council housing, putting solar PV on council houses, which are occupied by tenants (who choose the supplier, use the power and pay the bills), will give the council a benefit in carbon terms. Wrexham County Borough Council in North Wales, which fitted 3 MW of solar PV to its housing, is an example of this method.

Checklist for local authorities

The following is a brief checklist of the necessary ingredients for local authorities to address carbon offsetting successfully:

- climate change is an issue in local government that is rising in importance

- most local authorities have a climate change strategy or have made a climate emergency declaration

- most local authorities have set targets for a position of net zero carbon by a specified date

- most local authorities have some form of action plan in support of those targets

- in order to properly address climate change and work towards a target, the authority has to be in a position to know its starting point – hence a carbon footprint calculation or baseline

- the action plan will demonstrate the steps that can be taken to reduce the carbon footprint – included in an action plan are areas such as buildings, heating and transport where important changes will have to be made

- however, a rump of emissions that cannot be removed will be identified by this process

- carbon offsetting is a legitimate tool to be used by local authorities in dealing with this residue and meeting their targets

- a variety of methodologies can be adopted, from direct and indirect action by the authority to reduce its emissions, down to the purchase of offset credits generated by an external project

- the carbon footprint of the authority will be monitored and reported under this process, so that gains towards the target can be seen

- as the target date approaches offsetting activity might need to increase to meet the targets

- it is essential that offset schemes are properly managed and verified.

Offsetting using planning

Not all credit-based schemes are the same. Some local authorities are using the planning system in inventive ways in respect of offsetting arrangements. For example some local authorities (including Eastleigh District Council) – have set up nitrate credit schemes.

Residential development across the country, most significantly in the Solent region, has been blocked by the ‘nitrate neutrality’ issue whereby planning cannot be granted unless a development demonstrates that there is no likelihood of a significant adverse effect on any European designated nature conservation site.

This has essentially led to a moratorium on house-building in affected areas. Development may be permitted if the scheme is ‘nitrate neutral’, either through delivery of on-site or off-site mitigation.

Some planning authorities have now recognised the existence of ‘nitrate credits’ which can be purchased by developers to offset their nitrate production.

‘Nitrate credits’ are generated by third-party landowners who effectively agree with the local planning authority, through a section 106 agreement, to sterilise their land for use in ways which prevent nitrogen production. The land is attributed a number of ‘nitrate credits’ depending on its value which can be sold as an asset by the landowner to developers who can then demonstrate to the planning authority that their nitrate production has been offset such that the proposed development achieves ‘nitrate neutrality’.

Conclusions

There are many ways that carbon offsetting can be addressed by a local authority. However, some knowledge of how to do this and what good practice looks like will be required.

In our view, if carbon offsetting is required, it goes without saying that local projects in the UK should be chosen for this purpose, where it can be clear that the offset value is real, verifiable and sustainable.

There is a particular move towards nature-based solutions projects, such as tree planting, of which there are numerous examples. The Wildlife Trusts oversee a vast array of such projects covering areas as diverse as hedgerows, peatlands, coastal areas, grasslands, woodlands, wetlands and soils. According to its paper Let Nature Help, restoring our natural systems would provide 37% of the CO2 mitigation needed by 2030 under the Paris Agreement, but more importantly for local authorities, all of these schemes can be arranged locally, with wider benefits to the local economy.

As large landowners, every authority should be able to identify a local project they could lead that would provide an offsetting benefit. In some cases this can be made a ‘win win’ situation, such as where nature-based solutions (such as wildflower verges) are required under biodiversity strategies in any event.

It is still early days in local offsetting schemes but local government can lead the way in this space, by developing genuine and valuable projects and ensuring that they are verified and monitored for the benefit of both themselves and their communities.

Steve Gummer is a partner at Sharpe Pritchard LLP and Steve Cirell is a solicitor and consultant.

Free feasibility support

Get your Green Project off the ground with 10 hours free local legal advice.

We are committed to helping local authorities to meet their green goals and achieve their Net Zero targets. As part of this commitment, we are offering 10 hours of pro bono legal advice to one local authority each quarter on green projects in the feasibility phase. For further information and check eligibility please click here.

For further insight and resources on local government legal issues from Sharpe Pritchard, please visit the SharpeEdge page by clicking on the banner below.

This article is for general awareness only and does not constitute legal or professional advice. The law may have changed since this page was first published. If you would like further advice and assistance in relation to any issue raised in this article, please contact us by telephone or email

|

Click here to view our archived articles or search below.

|

|

ABOUT SHARPE PRITCHARD

We are a national firm of public law specialists, serving local authorities, other public sector organisations and registered social landlords, as well as commercial clients and the third sector. Our team advises on a wide range of public law matters, spanning electoral law, procurement, construction, infrastructure, data protection and information law, planning and dispute resolution, to name a few key specialisms. All public sector organisations have a route to instruct us through the various frameworks we are appointed to. To find out more about our services, please click here.

|

|

OUR RECENT ARTICLES

March 05, 2026

Reserve below-threshold contracts for UK or local suppliers under the 2026 OrderJuli Lau and Shyann Sheehy look into the impact of the Local Government (Exclusion of Non-commercial Considerations) (England) Order 2026, and particularly how local authorities can now reserve below-threshold contracts for UK or local suppliers.

March 05, 2026

CMO Principle and Financial Assistance Further Clarified in Latest CAT Judgment on Subsidy ControlBeatrice Wood and Oliver Dickie explore the key implications for public authorities following the latest CAT judgment on subsidy control (The Subsidy Control Act 2022: The New Lottery Company Ltd and Others v The Gambling Commission).

March 05, 2026

Make Europe Build Again – The EU Industrial Accelerator ActKamran Zaheer provides an insight into the anticipated “Industrial Accelerator Act (IAA)" and whether it will result in a “Made in Europe” regime.

February 24, 2026

2026 in construction: a look aheadMichael Comba and Rachel Murray-Smith provide a summary of the key points of interest in the upcoming year in the construction sector, predicting what will shape the future of this area.

|

|

OUR KEY LOCAL GOVERNMENT CONTACTS

|

||

|

Partner 020 7406 4600 Find out more |

||

|

Partner 020 7406 4600 Find out more |

||

|

Rachel Murray-Smith Partner 020 7406 4600 Find out more |

Catherine Newman

Catherine Newman